The Fabulous Bertha Palmer

Sunday, May 9, 2010 at 09:27AM

Sunday, May 9, 2010 at 09:27AM

The extraordinary life story of Bertha Honoré Palmer (1849-1918), Chicago heiress, philanthropist, champion for woman's rights, and innovative Florida developer, is also the story of America at the turn of the twentieth century.

In this charming 30 minute film, Mrs. Palmer and her son, Potter II talk about her life. The film takes the viewer from the days of her youth, through the Chicago Fire, to Europe and King Edward VII, and finally, to Sarasota, Florida. An American heroine, Bertha did it all.

"The Fabulous Bertha Palmer" is available for academic library and institutional purchase. Rights include classroom screening and closed campus streaming. Purchase price: $150.00

Academic rights INCLUDE the DVD with PPR and DSL. Use of third-party streaming services is OK. Academic licensees can also ask for a custom quote for single screenings.

If your system is not PayPal “friendly”, we will accept your purchase order or send you an invoice payable by check or credit card. For details on purchase orders, please contact: nagle.patrick@gmail.com

Story line details and Biography.....

From the Gold Coast to the Gulf Coast. . . The Fabulous Bertha Palmer

'The Fabulous Bertha Palmer' offers an intimate glimpse into a private, privileged world during the Gilded Age of the late 19th Century, set to the charming and eloquent music of that period.

In the Film, we listen to the ‘voice’ of Bertha Honoré Palmer in her own words, the legendary, larger-than-life queen of society, whose wit, charm, beauty, and daring endeared her to Presidents, Kings, heads of state, and the thousands whose lives she profoundly influenced.

We also hear from her adoring husband Potter, her son Potter Jr., and his wife Pauline Palmer. Their reflections on life with Bertha, based on letters, newspaper articles, fascinating archive footage and family photographs, beguile, amuse, and often amaze.

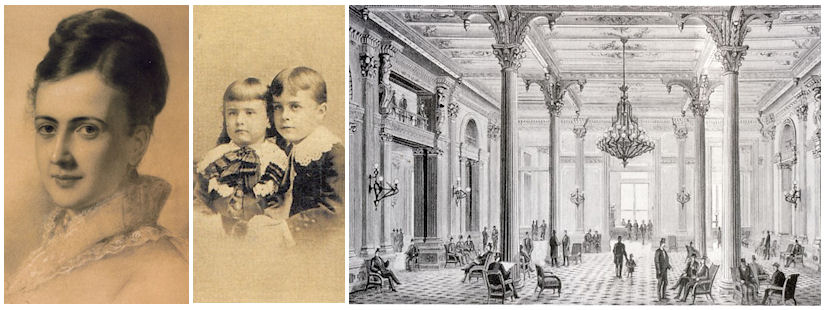

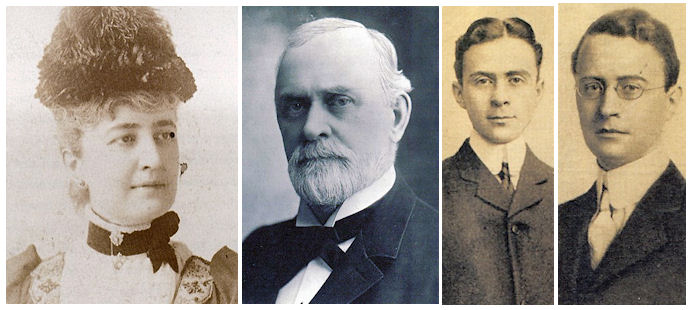

The Palmer Family on an outing. The boys, Honoré and Potter II, are young adults.

Completing the picture are films of the Palmers' vast land holdings and estates, their bequeathed art in museums, beautiful state parks and historic sites, along with interviews from descendants, biographers and historians and a narrative voice-over suppllied by an actor respected in the film industry.

This is not simply an entertaining inside story of a special lady who made her mark on the world, but of a woman at the center of an important part of American cultural and social history.

Though Mrs. Potter Palmer's name and image were known around the globe, long before the concept of international celebrity, it was in America where she made her indelible imprint.

Part I: Chicago: The Growth Years

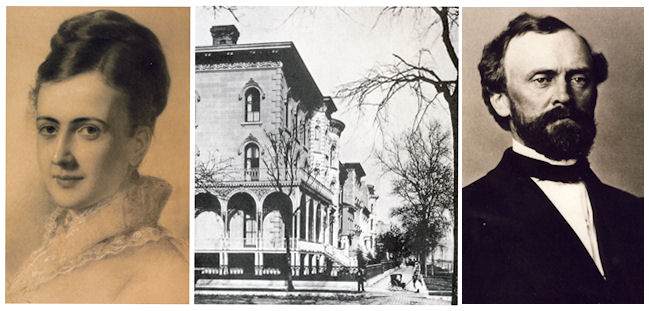

Bertha Honoré Palmer could have quietly enjoyed her cosseted life as the First Lady of Chicago society. Strikingly beautiful, stylish, strongly opinionated, and supported by the immense wealth of newly created American fortunes, she was doted on by husband Potter, a merchant magnate who had originally moved from New York to Chicago in the 1852, when it was but a wild prairie town.

The Honoré family had arrived at about the same time from Kentucky. When this charming Southern Belle first met Potter, who had become her father's business associate, she was only thirteen years old.

Potter was taken by the precocious young girl, who acquired an avid interest in business and politics, and often discussed real estate development with him and her father. Thought the most eligible bachelor in Chicago, he waited until Bertha made her debut at twenty-one before coming to court her. Older by twenty-three years, Potter's persistence eventually won her over. Despite the age difference they were well matched. Both possessed a keen intelligence and drive, though Bertha, nicknamed “Cissie” by her besotted husband, was extroverted, and loved to socialize, while Potter preferred his business pursuits.

Bertha and Potter married in her family home on Michigan Ave. when she was 21 and he 44.

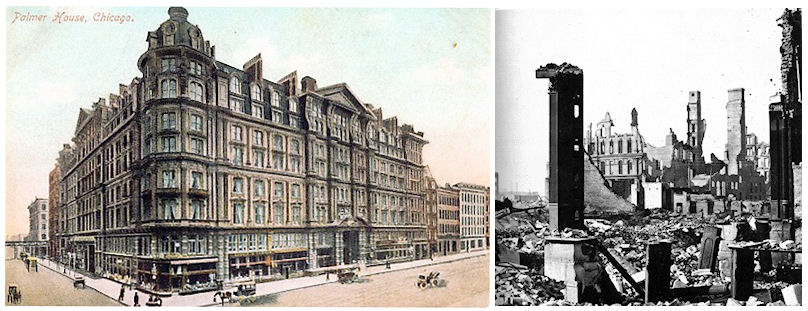

For a wedding present, he gave her his newly built Palmer House Hotel, which burned to the ground a year later in the Great Chicago Fire of Oct. 8, 1871.

Potter Palmer had been running a successful dry goods store selling the latest merchandise from Paris. He began offering credit, with a liberal exchange policy, which became known as 'The Palmer System'. Well, the ladies could not believe this delightful practice had not been thought of before, and simply flocked to his store, though one wonders if their husbands were quite so thrilled with the innovation. Soon, merchants from other cities came to study his progressive methods, including Macy's from New York.

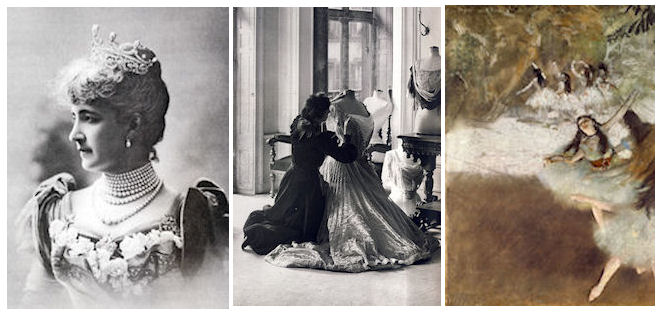

When Potter sold the business to Marshall Field, he used his sizable fortune to buy up real estate, and soon became Chicago's largest land owner. Real estate boomed, and Potter was a busy man, but he took the time to lavish upon his lovely wife gowns from Paris (she favored Worth), important art (she favored the Impressionists), and opulent jewelry (she favored pearls and diamonds). Her elaborate necklaces and tiaras were rivaled only by the collections of royalty. “There she stands,” Potter would proudly crow, “with $200,000 dollars on her!” Now wouldn't we all just love a husband like that?

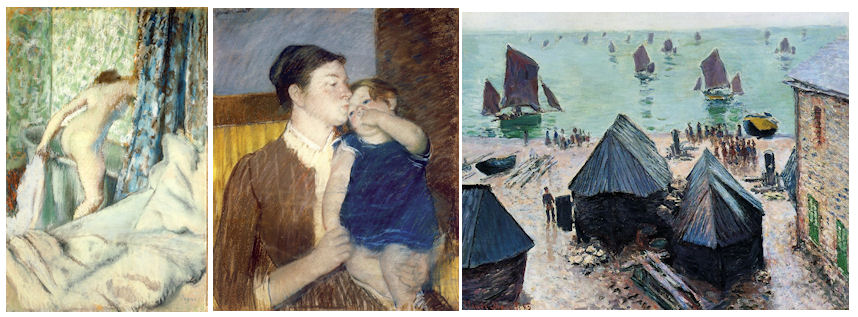

Mrs. Palmer favored pearls, Parisian couture from Worth, and the dancing queens from Degas, her first acquisition.

Bertha could have been simply a social gadfly. Instead the petite (5'5') wasp-waisted socialite dove eagerly into the world of business and politics, an intrinsic part of her life since childhood. Using her connections, she was able to help ease the plight of impoverished women and children, and improve the common-woman's appalling working conditions. In 1871, The Great Chicago Fire destroyed most of the city, including the Palmer House Hotel, which Potter had given his wife as a wedding present. However, Potter succeeded in rebuilding the hotel, “fire-proof this time.” Bertha moved in, gave birth there to sons Honoré and Potter Jr., and established herself as the leading lady of a society that had not even existed before the great fire. Invitations were coveted, especially when Bertha’s sister Ida wed Frederick, the son of President Ulysses S. Grant. Potter was offered the post of Secretary of Interior, but declined, preferring to run his own empire with his one true love and business partner, his wife.

Bertha gave birth to two sons in the elegant new Palmer House Hotel. What fun they had! The rebuilt Palmer House Hotel, 1874. The first “fire-proofed” hotel in America, it was even more luxurious than the original, and boasted silver dollars embedded in the floor of the barbershop.

Bertha gave birth to two sons in the elegant new Palmer House Hotel. What fun they had! The rebuilt Palmer House Hotel, 1874. The first “fire-proofed” hotel in America, it was even more luxurious than the original, and boasted silver dollars embedded in the floor of the barbershop.

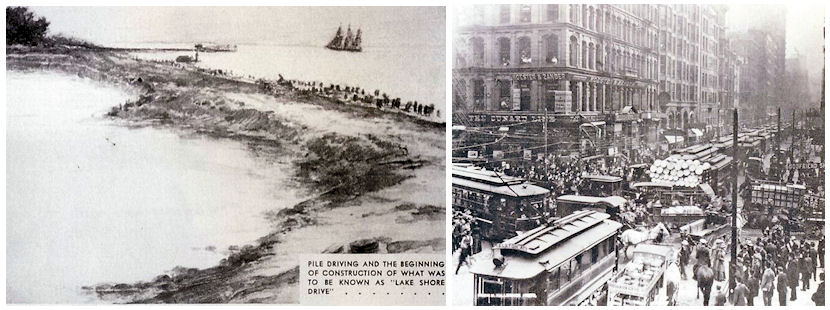

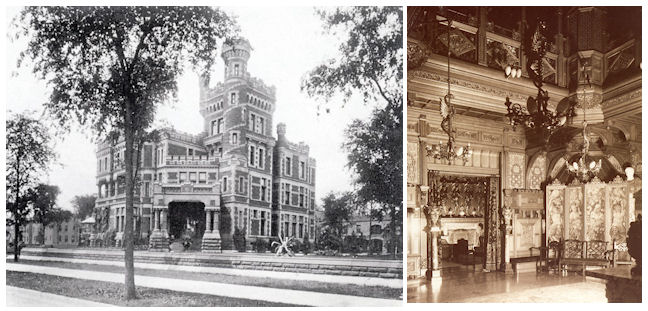

In 1882, Potter expanded his holdings and built 'Palmer Castle', a Gothic baronial pile on what would later become Lake Shore Drive. At the time barren and windswept, 'Frog Pond' was deemed a health risk. The area just north had been the site of a cemetery, filled with the shallow graves of victims of small pox and plague, and the skeletons of 20,000 bodies often inconveniently popped up. Potter's project was promptly dubbed 'Frog's Folly'. He ignored the ridicule. In buying up and dredging the marsh, and crusading against development by the Illinois Railroad, Potter succeeded in protecting the lakefront, and became one of Chicago's heroes. Soon, the rest of the social crowd began migrating north, despite the unsettling appearance of assorted bones and decayed coffin parts during various stages of construction.

Frog Pond was a far cry from bustling downtown Chicago, but Potter correctly predicted that people would tire of the sooty railroad, the smelly stockyards, and the crowded streets. He sold lots to friends, and hoped others would like the unobstructed view.

The opulent Palmer Castle, itself built entirely without outside doorknobs, was no doubt due to Mrs. Palmer's fame, but one does wonder. Her sons Potter Jr. (nicknamed 'Min') and Honoré had to knock to be admitted. The granite and sandstone Castle took up an entire city block, and was filled to the rafters with European antiques, priceless (and very progressive) Impressionistic art, and protective servants. Though disparagingly referred to as a “liver-colored monstrosity, turreted, and in the worst taste," it quickly became the most famous house in the city. Bertha and Potter played host there to presidents, kings, dignitaries, and the occasional accepted actress, such as Sarah Bernhardt.

‘Palmer Castle’, inside and out, was quite a piece of work. The interior was a mixture of styles; French drawing room, Spanish music room, and English dining room, where as many as fifty were regularly entertained at a seated dinner.

In these decades before women had the vote, Bertha, campaigning passionately for woman's equality, also made Palmer Castle available on numerous occasions for feminist meetings, and lectures to educate poor working girls. So what if a few silver spoons went missing? To cope with Mrs. Palmer's exhaustive social and charitable schedule of Castle events, Mr. Palmer would also often go missing, escaping in his private elevator, (the first in Chicago) to an eighty foot ivy-covered tower, the most dramatic feature of the Castle.

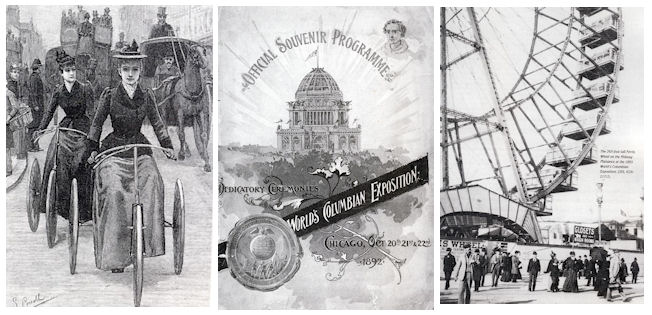

During those heady years, Chicago would become the fastest growing city in America, and witness a wave of inventions: Creative architecture boomed with the advent of the elevator, electricity was created, the phonograph patented, and the dishwasher, invented by (surprise!) a woman. The bicycle craze swept the country, and thanks to this new fad, as well as women entering the work force, fashions became more 'modern'. The century saw woman's increasing emancipation, and though Bertha claimed “not to be a suffragist,” she strongly felt that women had a rightful, equal place beside men in the world.

In 1892, American women were at last able to display their skills at the World’s Columbian Exposition

As usual, she put her thoughts into action. In 1891, when Chicago won the bid to host the World's Fair, she and her lady friends felt they could surpass the fabulous Paris Exhibition of 1889. Paris could have Gustave's Eiffel Tower. The 'World's Columbian Exposition', celebrating the 400th anniversary of Columbus' voyage to America, would have the amazing 265 foot Ferris Wheel, newly built by young George Ferris. Bertha threw herself into the project with her usual enthusiasm.

As President of 'The Board of Lady Managers', she chose 117 women from every state to work with her, including prominent civil rights leader, Susan B. Anthony, though officials had long been antagonistic toward suffragists. “Even more important than the discovery of Columbus,” Bertha proclaimed, “is the fact that the government has just discovered women.”

World’s Columbian Exposition, 1892. The Woman’s Building,left, was designed by young M.I.T. grad Sophie Hayden, who sadly had a nervous breakdown over the “hodge-podge” of donated items inside, and never designed another building.

Bertha traveled throughout Europe to solicit donations, and devoted an entire building to woman's industries and achievements from forty-seven other nations. Murals, Needlework art, sculpture, science exhibits and patented inventions such as the Hambell cake and egg beater, and a dress stand that converted to a fire escape, were proudly on display, though Bertha had to put her foot down with the lady embalmer who wanted to display a corpse! Otherwise, women from all walks of life were welcomed to submit their work. Bertha's advice to them, she took herself: “Keep up with the procession, and head it if you can.”

Mrs. Palmer and Her Ladies Lead the Parade for Women’s Rights

Mrs. Palmer led that procession, and her family followed. She, Potter, and the boys spent a good deal of time traveling, from the mansions of Chicago society to the luxurious resorts of Maine, to the royal homes of Europe. President McKinley appointed her to the National Commission representing America at the Paris Exposition of 1900, where she acted as ambassador for her fellow countrywomen.

The Paris Expo of 1900. Bertha was awarded the Legion of Honor by Emile Loubet, President of the French Republic.

The Paris Expo of 1900. Bertha was awarded the Legion of Honor by Emile Loubet, President of the French Republic.

Life in this gilded age was a whirlwind of formal entertainment, lavish ceremonies and transatlantic voyages, which naturally required an extensive custom wardrobe, and Mrs. Palmer made good use of Parisian haute couture. When devoted husband Potter died in 1902, no doubt of exhaustion, he left Bertha, then fifty-three, his entire estate of eight million dollars. His lawyers objected. “Your wife is a young woman,” they cautioned. “She may well marry again.” To which Palmer replied, “If she does, he'll need the money!”

Cunard’s Mauritania, “The Golden Ship”

Part II Europe: The Expatriate Years

Bertha took up homes in London as well as Paris, bringing along Potter Jr. (‘Min’), who was then twenty and Honoré a year older. She moved in King Edward Vll's charmed Marlborough Circle for the next eight years, the era of the Belle Epoque, achieving a place in European society rare for an American. Luckily, the widow Palmer, now one of the wealthiest women in America, could afford to dress the part. The opulent gowns, created for her by the appropriately named Worth of Paris, were made with the finest of brocades, silk satins, and hand-embroidered velvets, fitted to her tiny waist, and encrusted with rhinestones, pearls and glass beads. The exquisite collection of Tiffany jewels from her late beloved husband, the long strands of pearls, the diamond chokers, the tiaras and ruby rings and rare cameo brooches, all traveled with her back and forth across the English Channel.

Bertha conquers London, Paris, and King Edward VII. Center: his Paris townhouse

Bertha conquers London, Paris, and King Edward VII. Center: his Paris townhouse

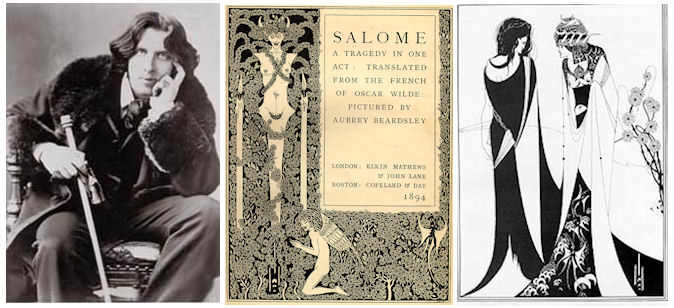

One event in her London home attracted great publicity, and horrified her brand new daughter-in-law. Pauline Palmer had only recently married the shy, mild-mannered 'Min', but had no idea what she was in for with his formidable mother. Bertha hired the Parisian cast of Oscar Wilde's new play 'Salome', (recently banned in England), to perform for her guests. As Pauline watched Maud Allen “dressed in chiffon and beads and nothing else, everything very visible,” she found 'Salomé' to be “so disgusting that I couldn't watch it.” London was “too horrible,” even though Pauline and Potter Jr. stayed at Claridge's Hotel, which was “quite grand.” She was also finding it “hell to be famous” as the new bride of Bertha Palmer's son, having been gawked at a great deal on their recent honeymoon voyage on Cunard's Mauritania. Young Pauline much preferred the tranquil beauties of Italy, though she found the Americans in Paris amusing when “they got drunk and began kissing and hugging each other.”

Wilde wrote Salome in 1892, with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley. First banned and panned, it was performed all over the world.

Wilde wrote Salome in 1892, with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley. First banned and panned, it was performed all over the world.

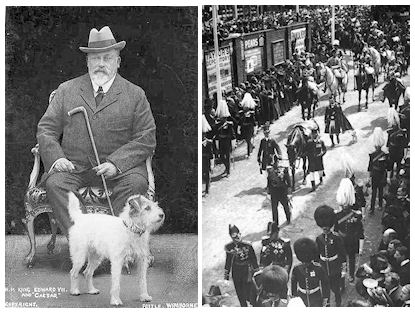

One doubts that the long-famous Mrs. Palmer spent much time worrying about the little quirks of Potter's delicate new wife. Though rumors abounded that Bertha herself would marry a title, she remained resolutely single, despite offers from assorted earls and dukes, including the Prince of Monaco and King of Serbia. Apparently there was only one king whose company she kept, often dining with him. Known to be a great admirer of American women, King Edward VII had a special place in his heart for the elegant widow Palmer, and his secluded townhouse in Paris, with its underground private passageway to ensure privacy, will not readily give up its secrets.

King Edward VII was considered quite a ladies’ man for his day, enjoying the company of more than one mistress..

King Edward VII was considered quite a ladies’ man for his day, enjoying the company of more than one mistress..

King Edward VII and his favorite companion, Caesar, who followed the King’s steed at the funeral.

King Edward VII and his favorite companion, Caesar, who followed the King’s steed at the funeral.

When the king died in 1910, Bertha Palmer returned to America, where she would embark on her next and final great adventure: The untamed wilderness of Florida.

View from Osprey Point, looking out on the undeveloped bay of Sarasota, circa 1910

View from Osprey Point, looking out on the undeveloped bay of Sarasota, circa 1910

Part III Paradise at Last: The Sarasota Year

Transcript of 'A Conversation with Bertha Palmer, The Queen of Sarasota'* written and directed by Catherine O'Sullivan Shorr,filmed in 2010 at Historic Spanish Point, former winter estate of Bertha Palmer

*Transcript of the completed short film:

(Written Across Screen)

When Chicago socialite Bertha Honoré Palmer arrived in Sarasota in 1910, it was a simple frontier fishing village, surrounded by vast tracts of swampy alligator and snake-infested marshland, filled with “mosquitoes of unprecedented size and viciousness.” She promptly fell in love, and purchased 140,000 acres. What on earth was the woman thinking?

Voice Potter ‘Min’ Palmer Jr.:

Before my mother became enamored with Florida, she had long been acknowledged as the fashionable 'Queen of Chicago', noted for her beauty, her wit, her fabulous pearls and diamonds, and the enormous Gothic Palmer Castle, where she and my father constantly entertained. Of her jewels, father would say, “There she stands with two hundred thousand dollars on her.” Mother often claimed, “The more you put on, the worse you look, the more you take off, the better you look.” I can assure you she did not often follow her own advice. But I soon came to realize that my mother was more than that. All those elegant balls she threw were for charity, the proceed going for her many causes. Our home was often filled with the voices of working girls, there for meetings and lectures. A few silver spoons were reported missing, but mother didn't mind. She was that rare breed of women born and married to wealth, who chose to use her influence to empower women less fortunate, as an advocate for their education and improved working conditions, an extraordinary undertaking for the 19th century.

Voice of Bertha Palmer:

I was not a suffragist! I simply felt that intelligent women could work with men to achieve their goals. I preferred diplomacy to balance the social and working worlds. Both my father and my husband had encouraged me to learn about business. I helped organize the Chicago Woman's Business Club in 1888 to help women entering the work force, and served as vice-president of the Civic Federation to bring capital and labor together. And oh my, what a time I had in 1892 with Chicago's first World's Fair! We'd won the bid to host the World Columbian Exhibition, to celebrate the 400 anniversary of Columbus' arrival in America, and as head of the Board of Lady Managers, I traveled abroad, meeting with many heads of state to present the works of talented women. Well, you can imagine, life was a whirlwind of ball gowns and grand soirées! But I always felt that culture, and society itself was a business, not a frivolity. When my dear Potter passed away in 1902, I was only fifty-three, Potter junior just twenty and Honoré a year older. I took the boys off to England, where we often dined with royalty, and they loved all the boat travel. But after a time, I was ready to come home. I was, after all, a businesswoman, anxious to explore new opportunities. And perhaps simplify my life a bit.

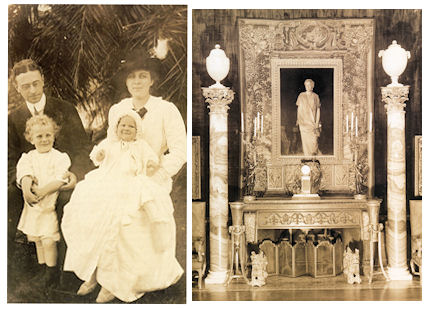

Bertha and Potter in their later years, with sons Honoré and Potter ‘Min’ Jr.

Bertha and Potter in their later years, with sons Honoré and Potter ‘Min’ Jr.

Potter ‘Min’ Palmer Jr.:

What prompted my mother's astounding decision to venture into an unknown jungle wilderness? It might have been the brutal Chicago winters, but she could have lived anywhere in the world, and often did. In England, she even took me with her on the maiden voyage of the 'RMS Lusitania' in 1907! My brother and I had a hard time keeping up with her constant travel, wrapped in jewels and yards of Paris finery. Rumors abounded that mother would marry a royal title; the Prince of Monaco, the King of Serbia, this earl or that duke. It was not to be. Back home at her own 'Castle' mother happened to read an advertisement in the Chicago Tribune for raw land opportunities in 'sun-kissed Sarasota'. She was ready to put her business acumen back to work, and build a winter haven for her fellow Chicagoans. In that respect, I suppose she could be considered a true visionary, because, Lord, they soon followed her in droves!

Bertha made a big splash when she and her two boys showed up in rural Sarasota.

Bertha made a big splash when she and her two boys showed up in rural Sarasota.

Bertha Palmer:

When I first arrived in Sarasota, I was immediately enchanted. The weather was too lovely. Here, at last was heaven! It quite reminded me of the Bay of Naples. I was taken with the quaintness of the local communities, the fishermen and the farmers. The hardiness of these frontiersmen reminded me of my dear late husband Potter, who was from a Quaker farming family in New York. He had come to Chicago in the 1850s when it was but a wild prairie town. My own family had arrived at about the same time from Kentucky, and I was brought up as an over-educated 'Southern Belle'. Business and politics were part of my life, and father had always discussed his real estate development ideas with me. I met Potter, his business associate at dinner, when I was thirteen, and I expect I was a bit precocious. By the time I made my debut at twenty-one, the dashing Mr. Potter Palmer came to court me. My dear, he was the most eligible bachelor in Chicago, though older than I by twenty-three years. Still, he cut quite a figure, and his persistence eventually won me over.

Potter ‘Min’ Palmer Jr.:

Father told me that he'd been so taken with mother that he had decided to patiently wait until she was of age to marry. By then he had become Chicago's biggest land owner, and in 1870, when they married, father built her the Palmer House, the grandest hotel in Chicago. Rudyard Kipling called it “a gilded and mirrored rabbit warren, crammed with barbarians.” I suppose he was thrilled that it burned to the ground a year later in the great fire. My father lost everything. Undaunted, he secured a loan and rebuilt the hotel, fireproof this time, and went on to develop the barren swamp land, around Lake Michigan, nicknamed Frog Pond. Everyone then called it 'Frog's Folly'.

Bertha Palmer:

Well, we had the last laugh, didn't we? When Potter Senior built me my beautiful 'Castle' there, doctors claimed the location was unhealthful, the winds off the water dangerous, so we were somewhat isolated for a while. But Potter was prescient; the social world eventually migrated north to make Lake Shore Drive the fabled 'Gold Coast'. Still, Potter junior has a point. The winter months can be bone chilling. One frigid day in January, when that little advertisement for a citrus grove caught my eye, I decided to investigate. I brought along my father, brother, and of course the boys, who loved an adventure.

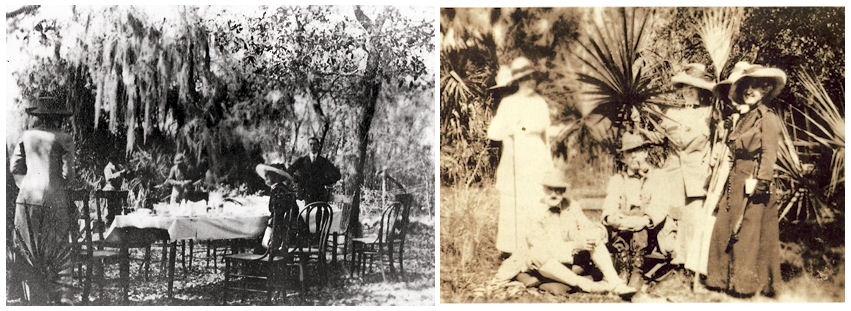

Bertha, family in tow, exploring her holdings along the Myakka River

Potter ‘Min’ Palmer Jr.:

Most of mother's friends thought she had lost her mind! We already had such magnificent, well-appointed homes in Chicago, Newport, Bar Harbor, London and Paris filled with antiques and fine art. Now we were heading off into unknown and possibly dangerous territory. But there was no talking her out of it. In total, mother's buying spree netted her roughly one-third of Sarasota County. I wonder what father would have thought of all this. Well, he had advised her to invest in real estate, but I doubt this is what he had in mind. (laugh) Father had been gone for eight years by that time, and against the entreaties of his lawyers had left mother his entire estate. “Your wife is a young woman,” they cautioned. “She may well marry again.” Father replied, “If she does, he'll need the money.” But as much as mother loved beautiful costly things, she was also a committed conservationist. On her own winter estate, 'The Oaks' in Osprey, she designed the most beautiful gardens and parks on those 350 acres, yet preserved the pioneer dwellings and prehistoric Indian remains.

The Oaks at Osprey, with its spectacular pergola and sunken gardens, framed by pre-historic Indian shell ’middens’. The Native-American era (3000B.C.-1000A.D.) was followed by the Homestead pioneer period (1867-1910). Then, along came Bertha.

Mother devoted 15,000 acres to ranching in the Myakka River area, and introduced important innovations to the citrus and farming industry, bringing in Midwestern technology, like vats to dip the cattle for ticks. She brought in Brahma bulls to breed with the scrawny creatures that roamed Florida back then, and soon had a magnificent herd. I can still picture her trudging around the muck of Meadowsweet Pastures in her simple farm dresses and boots, tending to the cattle and pigs, gardening, taking the grandchildren on picnics. But in the evening the Paris gowns came out for dinner.

Bertha (in right corner) feeds her pigs in the morning, and takes an afternoon boat ride in the bay. Note the cushioned chair.

Bertha’s family and friends enjoy an alfresco lunch at the mansion, and an adventure along the Myakka River

Bertha’s family and friends enjoy an alfresco lunch at the mansion, and an adventure along the Myakka River

Bertha Palmer:

Well, one has to observe the niceties of life. Even at the cottage, I was surrounded by favorite paintings, my Monets, Renoirs and Degas, whose favorite subjects dealt with dancers and brothels, but, my dear, so exquisitely rendered. Oh, and of course my friend Mary Cassatt, an American woman of exceptional talent who lived in Paris, because women did not have to fight for recognition there. I did cut down the amount of jewelry I wore, though I still treasured my cameo brooches, as one does. I was in my sixties now, and my priorities had changed. I chose family, not social acquaintances, to fill my days, and was well rewarded. I had much I wished to teach my grandchildren, and one becomes aware of one's mortality.

Degas’ ‘Morning Bath’, Mary Cassatt’s ‘Mother and Child’, and Monet’s ‘Departure of the Boats, Etretat’, from Bertha’s Collection

Degas’ ‘Morning Bath’, Mary Cassatt’s ‘Mother and Child’, and Monet’s ‘Departure of the Boats, Etretat’, from Bertha’s Collection

Potter ‘Min’ Palmer Jr.:

Mother passed away only eight years after she'd arrived in Sarasota. Her vast ranch land holdings along the river became Myakka State Park. Her treasured 'Osprey Point', later called Historic Spanish Point, with its gardens and fountains where we splashed in the heat of day, its lush jungles and charming 'beach cottages', was preserved as a popular tourist attraction. In the sixteen years since my father's death, mother had single-handedly doubled the estate he'd left her, and in those eight years of living in Florida, she'd molded her beloved Sarasota into an affluent, sought after winter destination, at the same time developing its ranching, farming and dairy industries. Mother brought her own unique vision to Paradise, and the Palmer family names on streets and neighborhoods are testament to her well-deserved title, 'The Queen of Sarasota'.

Portrait of “Queen Bertha” by Anders L. Zorn, 1893. Although her mansion was torn down in the early 1960s, the ‘Duchene’ Lawn and its classic portal were restored in 1980. The exotic jungle garden and formal sunken garden were also replanted to their original design, evoking the Gilded Age of Mrs. Palmer.

Bertha Palmer:

The 'Queen of Sarasota'? Oh, gracious, now you are embarrassing me, son. I will say that I have found my one talent, if I have any, at Sarasota Bay. It is beautiful to watch things grow, and see flowers blossom as I plant them. And thank you dear, for helping me to create the aqueduct, and my waterfall of seashells. I expect you were not quite thrilled at first, with neither fresh water nor electricity. Goodness! Nothing but swampy wilderness, just like your father found on the shores of Lake Michigan. But why were we here, after all, if not for that? This is Paradise; the bay, the sunsets, the fish leaping before one's eyes, the cacophony of tropical birds, who seem to get along just fine with their winter visitors...We are all migratory birds of a feather, are we not, searching for a brief resting place?

Bertha walks off into the Sarasota sunset with son Potter and grandson Potter III

Bertha Honoré Palmer died of breast cancer on May 5, 1918, in her mansion at The Oaks, on Osprey Point. She was 69. On news of her death, the Herald Tribune printed: “There can be no grief, at the end of such a journey.” Sarasota's flags were flown at half-mast to honor the woman whose extraordinary vision had transformed their sleepy fishing and farming community into a vibrant cultural center.

Epilogue: Return to Chicago

As late as May 1, 1918, Bertha Palmer had expressed every intention to return to Chicago to help with the war effort. For two years she had been fighting cancer with the same determination she put into every project, traveling to New York to have a mastectomy, and promptly returning to Sarasota to direct work at her ranch. But one understands the limits of medical treatment one hundred years ago, even to those with unlimited resources. “When she no longer toured her property and the workmen saw no more of her, the story was whispered about in Sarasota that Mrs. Palmer was dying of cancer.” With her when she died were her sons and their wives, her brother Adrian, her sister Ida, who was married to the son of President Ulysses S. Grant, and Ida's daughter and husband

Mourning crowds gather outside Palmer Castle on the day of Bertha’s funeral, 1918

Mourning crowds gather outside Palmer Castle on the day of Bertha’s funeral, 1918

Her body was brought back to Chicago for the funeral at the Castle, where her coffin lay in the famous gallery. Her sons made sure that a blanket of her adored Florida orchids covered the coffin. Outside in the street, crowds gathered to pay their respects. The funeral was simple, as Bertha had wished, but impressive. Among the dignitaries, politicians, and captains of industry were the multitudes of women whose lives and well-being Bertha had championed for so many years, who had called her “The Queen of Womankind of the World.”

The Castle and its three story Gallery, where Bertha showed off her art collection, and where she lay in state upon her death

The Castle and its three story Gallery, where Bertha showed off her art collection, and where she lay in state upon her death

In her will, Bertha left close to $20 million, most of it in trust to Min and Honoré. Included was the Palmer House, the Castle, and 150 pieces of property she had inherited from her husband. $100,000 was left to each daughter-in-law. She bequeathed her Sarasota cattle ranch to brother Adrian, and stipulated to her sons that fifty-two paintings from her collection be given to the Art Institute of Chicago. Years later, a visitor remarked that “All those Renoirs must have cost the Institute a fortune.” The President of the Institute replied, “In Chicago we don't buy Renoirs, We inherit them from our grandmothers.”

Pierre August Renoir’s Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise, 1874

Pierre August Renoir’s Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise, 1874

Potter Jr. bought out his brother's interest in the Castle, and he and Pauline moved in. Rather mild and reticent like her husband (Potter Jr. appears to have taken after his father and married a kindred spirit), Pauline gamely took up the mantle that Bertha had laid upon her shoulders, opening Palmer Castle to the Red Cross and working for the war effort. Bertha would have been a hard act to follow for even the staunchest daughter-in-law, but Pauline, whose own style would be compared to Bertha, entertained “with impeccable taste rather than on a grand scale,” meaning she preferred “intimate gatherings” to her predecessor's lavish events.

Pauline and Potter Jr., with Potter III and Bertha in Sarasota. Portrait of Pauline, after she and ‘Min’ moved into the Castle

Pauline and Potter Jr., with Potter III and Bertha in Sarasota. Portrait of Pauline, after she and ‘Min’ moved into the Castle

Pauline Palmer and friends enjoy Crescent Beach on Siesta Key. Five years after Bertha’s death,, how the fashions have changed!

Pauline Palmer and friends enjoy Crescent Beach on Siesta Key. Five years after Bertha’s death,, how the fashions have changed!

As prominent members of Chicago's “first family” and a firm presence in Sarasota, the next generation of Palmers would enjoy their prosperity and bring up a family of four, naming the first son, naturally, Potter III, and their daughter Bertha after her doting grandmother. As overseer of the family's vast real estate holdings and important art collection, Potter Jr. would diligently protect his mother's legacy, and wisely shepherd it from the end of the Gilded Age into the modern age of the twentieth century. The larger-than-life matriarch of the Palmer dynasty who had “headed the procession” for so long, would go on to have a multitude of books and stories written about her. . . . This is the one to be filmed.

Bertha Honoré Palmer, 1893, created by Stein and Rosch Fotografers, New York Public Library

Bertha Honoré Palmer, 1893, created by Stein and Rosch Fotografers, New York Public Library

Note from the author

As a grateful survivor of breast cancer and today's state-of-the-art treatments, I found myself in admiration of the Bertha Palmer I encountered in the many books and news articles written about her. Through her exploits, adventures, and accomplishments, I sensed an indomitable 'frontier' spirit, and a graceful courage in the face of what in those days could only be a death sentence. Bertha, you inspire me, as I expect you will many others.

-Catherine O'Sullivan Shorr, Sarasota, Florida 2013

Acknowledgments

The Art Institute of Chicago

Hans Johnsson, Founder/Coordinator Bertha Palmer 2010 Centennial

Jane Kirschner, Board president, Sarasota Historical Society

Gulf Coast Heritage Association Inc.

Linda Mansperger, Executive Director, Historic Spanish Point

Timothy A. Long, 'Bertha Honoré Palmer'

Ernest Poole, 'Giants Gone-Men Who Made Chicago'

Isabel Ross, 'Silhouette in Diamonds-The Life of Mrs. Potter Palmer'

Sally Sexton Kalmback, 'The Jewel of the Gold Coast, Mrs. Potter Palmer's Chicago'

Eleanor Dwight, The Letters of Pauline Palmer

Reader Comments