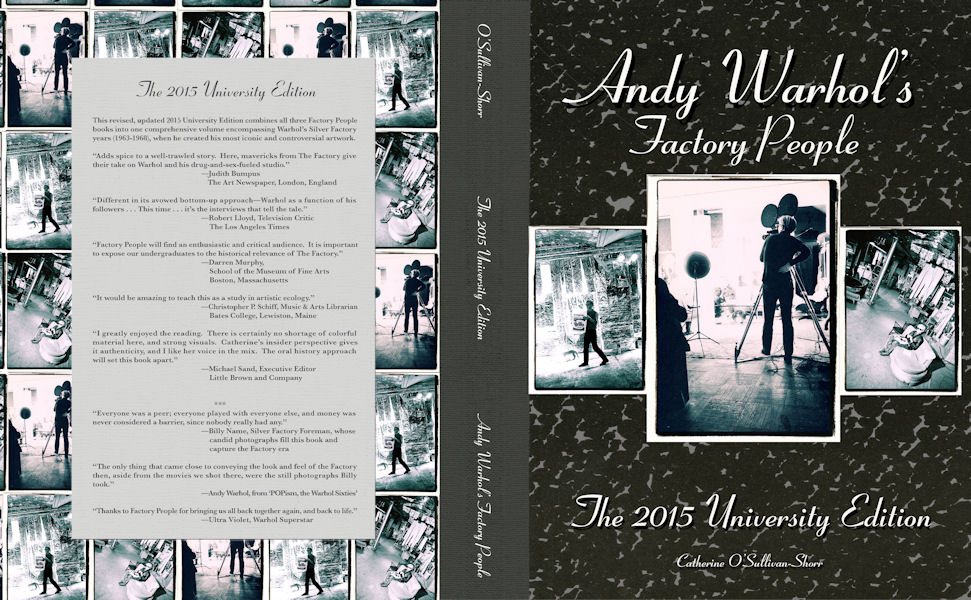

Andy Warhol's Factory People Book...2015 Revised University Edition

Monday, August 20, 2012 at 06:15PM

Monday, August 20, 2012 at 06:15PM

The ‘Factory People’ 2015 Revised University Edition is an updated 439 page oral history of Warhol’s life and career trajectory during the Silver Factory era, as told by those who were there with him at that seminal time. The genre's literary nature-not just its capacity to tell sweeping, timeless human stories, but also the craft and cunning involved in its artful assemblage of specific, individual voices, sets this book apart from all others about Andy and his New York in the 60s.

‘Factory People’ covers the years 1963-1968 in New York City, when Warhol created the Silver Factory, and his most iconic works of art. He also found time to make famous a little-known group called ‘The Velvet Underground’, and to make movies, movies, and more movies.

Catherine and the Book...

Catherine and the Book...

Edited and written by Catherine O’Sullivan Shorr, director of the lauded television mini-series, the book is based on fifty hours of fascinating interviews with those who worked with, partied with, and passionately loved Warhol during his most prolific (granted, also his most scandalous) period. Yet few would argue that the Silver Factory, with its taciturn ‘King’ and his devoted subjects, was a true groundbreaker, playing an invaluable role in the cause of creative freedom and gay rights, or as Billy Name, Factory photographer, would say, “Just living people rights.”

NOTE: Now students and faculty can purchase this edition directly on Amazon for $49.95 plus shipping.

Here is a promotional film about the books based on a recent interview with BBC Radio.

The different voices in this book are all great storytellers. Whether wickedly funny or acidly bitter, they reveal the different sides of Andy Warhol, public and private. He could be charming and beguiling to some, cunning and manipulative to others. He could be stingy; he could be generous to a fault. Some found him supportive, while others bemoaned his seeming ignorance of the needs of those around him. Well, as Lou Reed (‘The Velvet Underground’) once succinctly put it: “The Silver Factory is not a Mental Hospital.”

The Factory People University Edition is a bound/soft cover 8x11 and it includes: Book I "Welcome to the Silver Factory" (143 pages); Book II "Speeding into the Future" (143 pages); Book III "Your 15 Minutes Are Up" (143 pages). The Edition includes over 500 photographs by Billy Name, Nat Finkelstein, Steven Schapiro, and others.

Purchase Andy Warhol's Factory People (The 2015 University Edition Book) PDF for download to your system. $50.00 Please note that this purchase requires that you provide us with an email location so that we can send you a link to our PDF location on the DropBox system.

NOTE: Purchase can also be made by Check. Send us your PO and we will Ship and Invoice at the same time. All sales are NET 30 days. For more details please contact nagle.patrick@gmail.com

You can also purchese the EBOOKS here...

Andy Warhol's Factory People E-books for students and individual faculty are available from Amazon, Kindle, I-Book and others.

A few reviews and comments...

Robert Lloyd, television critic for the LosAngelesTimes, called the Series “…different in its avowed bottom-up approach: Warhol as a function of his followers is the idea…this time the interview subjects get to talk about themselves and each other…it’s the interviews that tell the tale.”

According to Judith Bumpus of London’s The Art Newspaper: “ The Factory People Film series adds spice to a well-trawled story. Here, mavericks from the Factory give their take on Warhol and his drug-and-sex-fuelled studio.”

Recently, Michael Sand, Executive Editor for Little Brown and Company commented: “Pat Strachan has shared Catherine O’Sullivan Shorr’s Factory People (book) proposal with me and I great(ly) enjoyed reading (it). There is certainly no shortage of colorful material here and some strong visuals. Catherine’s insider perspective gives it authenticity, and I like her voice in the mix. The oral history approach will set this book apart.”

Catherine interviews Filmmaker Jonas Mekas...for three hours.

Catherine interviews Filmmaker Jonas Mekas...for three hours.

“It would be amazing to teach this as a study in artistic ecology. Andy couldn't have done what he did without his amazing circle, and the circle makes sense only in the light of his special form of patronage.”-Christopher P. Schiff, Scholar and Performance Artist, Music & Arts Librarian, Bates College

"I’m confident that “Andy Warhol’s Factory People” will find an enthusiastic and critical audience here at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It is important to expose our undergraduates to the historical relevance of the Factory." -Darin Murphy, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Author and her Producer...P.S. 260 Studios, New York City

The Author and her Producer...P.S. 260 Studios, New York City

Here is the introduction to the book published in its entirety:

Art colossus Andy Warhol once said of his detractors, “I don't understand. Everything you do is real, is right.” We made that pithy statement the theme for our television documentary series, ‘Andy Warhol’s Factory People’. For that reason, we began our film toward the end of the ‘Beat Generation’, when a frustrated graphic artist from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania announced he was “starting pop art” because he “hated” Abstract Expressionism. No one took him seriously. It was 1960, after all, and power-houses like Jackson Pollack, Yves Klein, Jasper Johns and his companion Robert Rauschenberg were the undisputed stars. Warhol’s maiden attempts were rejected; he was rejected. Others might wait for a more favorable climate. “They always say that time changes things,” he was heard to say, “but you actually have to change them yourself.” That summer, Warhol painted a six-foot tall picture of a coke bottle. Though he feared people would dismiss him as a commercial artist, Warhol’s innate gift lay in calling upon everything he had learned from advertising. And in absorbing ideas from everyone and anyone who wandered into his special world. “Paint something that everybody recognizes,” offered interior decorator Muriel Latow, “like a can of soup.”

Andy and his Bananna...paint something everybody recognizes....

Andy and his Bananna...paint something everybody recognizes....

ANDY WARHOL’S FACTORY PEOPLE is the true story of Warhol and his entourage of misfits and muses, who found themselves at the cutting edge of New York’s art scene in the sixties, like poet Gerard Malanga, who started with Warhol as a silk-screening assistant. Soon after, theatrical lighting designer Billy Linich created Warhol’s cavernous work space’, and slathered it all in aluminum foil. Linich, now renamed, uh, Billy Name, became the official in-house photographer. He had subjects aplenty; the new ‘Factory’ filled quickly with a wild collection of characters, all about to become famous for fifteen minutes.” This book is the culmination of shooting fifty hours of those interviews, screening over a hundred hours of Warhol's movies and screen tests, collecting archive and news footage, sifting through thousands of Billy Name photographs from his fabled collection, and running up copious bar tabs in New York, Los Angeles, Paris, and London.

OvationTV broadcast the Series in the USA on Thanksgiving Day as part of their original channel launch in 2008. The Series went on to run in over fifty international territories and has been licensed to over 400 colleges and universities around the planet.

OvationTV broadcast the Series in the USA on Thanksgiving Day as part of their original channel launch in 2008. The Series went on to run in over fifty international territories and has been licensed to over 400 colleges and universities around the planet.

The project started out as a three one-hour television episodes spanning1964 to1968, four crucial years in Warhol’s legacy, and arguably his busiest and most creative period. Not coincidentally, it also took us four frenzied years to complete our project, waaaaay past our network's deadline, having endured a stunning series of mishaps, meltdowns and sheer madness that felt downright 'Warholian', and made me want to take up drugs again. . .

"The different entourages that dominated the sixties, like Leary’s, or Ginsberg’s, or Warhol’s or Dylan’s, had to do with drugs and people’s attitudes toward drugs." —Victor Bockris, Biographer, ‘Andy Warhol’

Catherine O'Sullivan in the 60s, Provincetown, Mass.

Catherine O'Sullivan in the 60s, Provincetown, Mass.

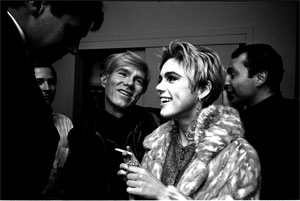

In the sixties, I found myself a part, albeit peripheral, of Warhol’s Silver Factory 'Family', and an even more obscure remnant of Dylan’s entourage. Through a summer folk-singing stint at the Blues Bag in Provincetown, Mass, I met and befriended and smoked with Richie Havens, Muddy Waters, and most everyone who passed through. Mellow, mellow. Then, whoa! Warhol and the Velvet Underground arrived to play at the Chrysler Museum. The police closed the show down, but I was thrilled to have them visit my place, just down the road from mega sculptor John Chamberlain and macho writer Norman Mailer. I did not realize at the time that the toilets in their rental house had backed up and they needed facilities.) The Velvets did appear a bit sinister for summer, all dressed in black and “looking like the death crew,” as Warhol Superstar Mary Woronov would say. They had nothing but amused disdain for our tie-dyed psychedelica, Buddhist bells, and sandals. That's what was so wonderful and indicative of the time—you could change at a moment's notice and become someone else, even if you were already famous. Steve McQueen was racing Walter Chrysler's prototype Turbo down the road to Land's End, where Marlon Brando was staying with his pal Wally Cox, and we somehow all wound up there. Warhol was not a fan of hippies, nor of a certain Dylan song that had supposedly been directed at him. Our 'Napoleon in Rags’ sequestered himself in the bathroom and powdered his blotchy, pockmarked face and blond wig with talcum, leaving residue simply everywhere, which I mistook for cocaine and snorted off the toilet seat. I didn't realize at the time that Warhol considered himself unattractive, and was thus attracted to pale, frail-looking people like himself (Edie Sedgwick,) or tall, aloof Teutonic blondes (Baby Jane Holzer, Nico) because he wanted to literally be them. Well, we all wanted to be Nico, except, it turned out, Nico herself. Born in Nazi Germany as Christa Paffgen, she'd escaped to Paris and Rome, and appeared in Fellini's 'La Dolce Vita' at fifteen. I worshiped Nico—the Irish tend to get on with Germans for reasons best left to British history—and took her succinct advice regarding wayward boyfriends and babies. I was happy to watch after Ari, her toddler son by the French actor Alain Delon, who would toddle off toward the ocean and worry everyone except his nonchalant mother. Nico, like the rest of the Warhol crowd, was older, mysterious, and impossibly cool. Her flat baritone, her surreal beauty, in perfect sync with Lou Reed's nihilistic lyrics, mesmerized us. We copied her platinum curtain of hair, peroxiding and ironing our locks into lanky submission, until the marine layer moved in and undid it all. Warhol had no such problem. He wore his wigs firmly attached to little clips imbedded in his skull, and had a bottle of peroxide handy for infection, which everyone used.

Andy loves Edie...

Andy loves Edie...

Warhol's previous ‘Girl of the Year’, the charismatic and doomed Edie Sedgwick, with her tiny dresses, boyish hair, and enormous chandelier earrings, had dropped from favor. According to Warhol, who equated stardom and glamour with its inevitable demise, his ‘Girl of the Year’ would only last that long in the spotlight before succumbing to exhaustion, drugs, or insanity. He was so often proven right. His women were beautiful, and usually from good families, generous free spirits with trust fund money to burn until it ran out. The men, on the other hand, were for the most part itinerant hustlers, juvenile delinquents and pretty rent boys from poor backgrounds. The exceptions were Warhol’s trusted trilogy of Billy Name, Gerard Malanga, and Ondine, who comprised a kind of royal court for their ‘King of Pop Art’. I didn’t get Warhol’s art. A Brillo Box? A silk screen of a soup can? I thought anyone could do it. But no one else did do it, so Marcel Duchamp was right all along about him.

Andy filming Marcel Duchamp.

Andy filming Marcel Duchamp.

At the end of that eventful summer, I went back to college in sunny Mexico, to mescaline, marijuana, and peyote. Money was scarce, but psychotropics plentiful. Warhol and the Velvets went home, back to the New York underground, amphetamine and heroin. Hopscotching, (well, tripping) through a couple of years, I would not see them again until early ‘68, in Max’s Kansas City on Union Square near Warhol’s new ‘White Factory’. The back room had become the Factory ‘commissary’, but Max’s served as a second home for the rest of us— a lax one— where we could leave all cares and inhibitions (and sanity) at the door.

Valerie Solanis brought about the END of the Silver Factory era.

Valerie Solanis brought about the END of the Silver Factory era.

But for the Silver Factory coterie, much had changed. Their ranks had been decimated by overdoses, suicide, banishment, or a falling-out over money. Warhol had talked legendary Taylor Mead into coming back from his wilderness years in Paris, to star in films with Viva, the vivacious (and sometime vicious) ’Lucille Ball of underground movies’. Though he wasn’t paid any better, Taylor got to hang out at Max’s with emerging Superstar transvestites Holly Woodlawn, Jackie Curtis and Candy Darling, and charge it all to Andy, who sat nearby with Nico, now estranged from the Velvet Underground. I didn’t recognize her at first. The glorious sheaf of golden hair had been dyed a dirty orange mat, her skin looked sallow, her eyes haunted. Nico had considered her beauty a curse, distracting from her from her true passion, singing. Now she sat between Warhol and Ondine, chain-smoking, stoned, staring into space. Edie Sedgwick was also gone, also wasted on heroin. As other Factory members met the same fate, the wags were blaming Warhol. His image of ‘father figure’ to misfits had morphed into something more sinister. He was called a vampire, a voyeur, and a corrupter of youth. He'd become his own bogeyman, berating himself to confidants over his apparent lack of empathy, but doing little to convince detractors otherwise. According to those close to Warhol, “People had begun to actually hate him.”

All Tomorrow's Parties...

All Tomorrow's Parties...

Even before Warhol was shot by a disturbed Valerie Solanas in 1968, we could feel the subtle difference in the air, that uneasy combination of dread and malaise. The ‘Summer of Love’ slid into something mean and scary, though for a while we put it down to overactive imagination. But the truth was that soft drugs had gotten hard, and so had a lot of the people.

When 1969 arrived, the hippies among us headed for Woodstock, free love, and naked groveling in the mud. Warhol and company, in an attempt to generate income, staged a series of male porno films at a hardcore film house. The expected clientele would come to Andy Warhol's Theater: 'Boys to Adore Galore' and leave at the happy ending, but in an effort to go a bit upscale and have cleaner floors, he and Paul Morrissey began work on the aptly named 'Trash' and 'Flesh'. Those hilarious, heartbreaking films, and a retrospective of the art he had done when he “retired” from painting in '66, would finally bring Warhol his 'overnight' success as a filmmaker. Jonas Mekas, revered father of underground film, compared Warhol to Godard, Renoir, and Eisentstein, but most people could barely sit through the endless hours of poorly lit, improvised, unedited, and sometimes pornographic footage that comprised a Warhol work. I know the feeling—I watched at least 100 hours of films to find the few minutes used in our documentary. Jonas had a point. No one could make movies like Andy Warhol. . .

Giving up painting for filmmaking...

Giving up painting for filmmaking...

Fast forward forty or so years, and I don't think anyone could make a movie like ours, either. After countless career changes, countries, husbands, wives and lovers blah blah (This book is about Warhol, not us), your filmmakers found themselves together again at last in Paris, home of Cinéma Vérité, writing and making movies and documentaries with considerably more freedom, and government money, than one could hope for in the Hollywood studio system to which I'd been tethered for decades. (Don't rush off to Europe just yet. It helps if you speak the language and have an E.U. Passport; otherwise you're just another expat trying to pass). We'd already been working awhile when approached by a TV network to do a series on the arts, and Warhol in particular. So, voilà! With my fifteen minute memory of Warhol, I worked up a proposal covering what could be considered the most pivotal period in Warhol's artistic career—The Sixties.

Billy Name being interviewed...for four hours in New York City, 2007

Billy Name being interviewed...for four hours in New York City, 2007

Much of Warhol’s life has been already examined in minute detail. When we decided to make this documentary, we felt that it would be interesting, and probably more entertaining, to hear not from the ‘experts’, but from those dreamers who had been at the Factory from the beginning, and who had followed Warhol’s phenomenal trajectory into fame and notoriety. We were not disappointed. Any preconceptions of Warhol that we may have harbored were jettisoned—along with our initial budget—when we began interviewing those who worked with him, amused him, abused him, loved him, and feared him. Our resultant film series disclosed new insights into this complicated artist's life, and opened a Pandora’s Box of contradictory stories remembered by his many muses, his few close friends and fewer confidants.

Let's make 500 of these this week...it's easy to do!

Let's make 500 of these this week...it's easy to do!

I've been told it's impossible to unearth the true character of any man, woman or dog without talking to them, but I've often felt myself to be in dialogue with the elusive 'Drella', especially at trying moments in this project (the theft of original masters, the disappearance of money, the breakdown of umpteen editing bays, the tearful screaming fits, and firings of assorted editors, oh, I could go on. . .) Fortunately, we were saved by Warhol’s ‘Factory Family’ and their formidable collective memories. Because they had, indeed, talked with him, All The Time, we were given an indelible portrait, and quite a complicated one it is. The finished series was not what we expected, but it must work; since we completed and aired our 'Factory People' series, other Warhol 'specials' have cropped up using our format. Is imitation really the sincerest form of flattery, or are they just too fucking lazy to do their own work? Oh, Warhol would probably approve; he loved repetition. . .

Having fun impersonating Warhol, and getting paid for it....

Having fun impersonating Warhol, and getting paid for it....

At the end of the day, what did we learn from all of our Factory People? We discovered how easy it was to create an Andy Warhol work of art, how easy it was to steal an Andy Warhol work of art, and how easy it was to literally become Andy Warhol himself, and get away with it. All, it would seem, with Warhol's tacit approval. As for the odd circumstances behind his horrific near-fatal shooting, which appears to be a probable cause of his subsequent decline as an artist (and later his ‘sudden’ premature death), those Warholian moments became clear in our interviews, where the most oft repeated words were, “Fame”, “Fifteen”, and “Superstar”.

So, was Warhol a hated demon, as often portrayed, or a beloved savior to his motley group of creative misfits? Both, it seems. In certain families (or cults) it can be a slippery slope from initial attraction to eventual abuse, and those who were part and parcel of Warhol's collective success were, in the end, betrayed. They were summarily ejected from the Factory. Not a fairy tale ending for anyone, least of all Warhol.

Sooner or later it all had to come to an end....

Sooner or later it all had to come to an end....

Some would say—ourselves among them—that Warhol’s work after the Silver Factory rarely if ever reached the marvelous heights of madness and brilliance achieved through the collaborative efforts of all those loony drugged geniuses that floated through his freight elevator doors on 47th Street. One by one they left the fold, under the watchful surveillance of the F.B.I., who'd been busy hounding them for more than a year, trying to pin charges of pornography, rape, and drug abuse on 'Drella' and entourage. The Silver Factory story ends with the shooting of Andy Warhol in 1968 by Valerie Solanas, the unstable lesbian feminist writer whom Ultra Violet thought “demented, of course, but with an interesting philosophy.” Warhol had put Solanas to work acting in the film 'I, A Man' and her footage, which we included in our series, is revealing in a most unexpected way. Unfortunately for both, Warhol had forgotten to return or simply mislaid a screenplay she'd given him, entitled 'Up Your Ass. Grounds for murder? Well, as Taylor Mead put it, “Andy did make promises. I wrote a critique of the movie ‘I Shot Andy Warhol, and I titled my article 'I would have shot Andy Warhol'.” Taylor was only half- joking. In Warhol's over-the-top world of bisexual, bipolar fantasies, the fabulous craziness had finally spilled over into pathology. Hence the arrival of the suits to the new 'White Factory' on Union Square, nice people, hip and efficient and certainly more practical, and since they upon occasion suffered the same ‘palace’ intrigues as the old court, it would be churlish to resent their astounding success with packaging and selling Warhol. But hey, this isn’t their story—that would be a bit predictable.

Andy made it all look so simple...he had a lot of help...

Andy made it all look so simple...he had a lot of help...

A grateful “Merci” to the marvelous Warhol Museum, to the wonderful and weird archival footage folk who dug up buried treasures from the 'Happening Sixties', especially when Warhol and his Silver Factory made the news, and to Vincent Fremont, founding director of The Andy Warhol Foundation For the Visual Arts, for his expertise and help with the Warhol Foundation. . . Most of all, a “Merci bien” to Billy Name and the Factory Family, who gave up to Andy so much of their lives, and who graciously gave me so many hours of their time. I feel I have become a part of that family, celebrating their late-in-life accomplishments, and, for some, attending their funerals. Their lives were a celebration. At the end of the day, how many of us get a full page and photo-op in the obits of the New York Times?

—Catherine O’Sullivan Shorr, Paris, France, 2012

Cathy and sister Maureen attend a party at the American Ambassador's residence, Paris November 2011.

Cathy and sister Maureen attend a party at the American Ambassador's residence, Paris November 2011.

P.S. I have tried (and failed) to keep my voice from intruding in these edited interviews, which have become interwoven with, well, me. I would prefer to remain under the radar, but thought it helpful to connect some of the dots, accomplished without narration for the film. My input is betwixt the --- s, so you can easily skip over them. Please don’t.