The Gerard Malanga Interview

Get the University Edition Book on Amazon HERE

Our three hour film, “Andy Warhol’s FACTORY PEOPLE”, tells the story of the 60’s Silver Factory that Andy founded in 1964 in an abandoned hat factory on East 47th Street in New York City. The Silver Factory lasted until 1968 when Andy gave up the lease and moved to the White Factory on Union Square. Shortly after moving in the Spring of ’68 Andy was shot by Valerie Solanis and this event bookends the period of time covered in “Factory People”.

Our three hour film, “Andy Warhol’s FACTORY PEOPLE”, tells the story of the 60’s Silver Factory that Andy founded in 1964 in an abandoned hat factory on East 47th Street in New York City. The Silver Factory lasted until 1968 when Andy gave up the lease and moved to the White Factory on Union Square. Shortly after moving in the Spring of ’68 Andy was shot by Valerie Solanis and this event bookends the period of time covered in “Factory People”.

The idea of the film is to tell the real story of the culture, who was there with Andy, who participated in the work with Andy, and what really happened.

Can you start at the beginning?

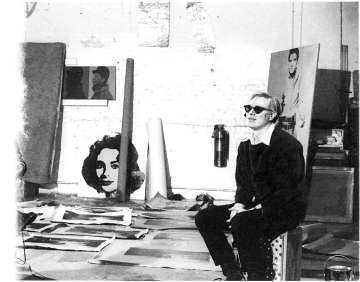

"My name is Gerard Malanga and I am a poet and a photographer and a film maker, and I have been at it, started writing poetry in 1959, published my first works in 1962, in 1963. I was introduced to Andy Warhol who hired me as his silk-screen assistant and we silked-screened many important paintings between 1963 to 1967 and a little bit into 1968.

Gerard silk-screening with Andy.

I grew up in the Bronx, I was a first generation American Italian. Grew up in very modest circumstances, went to an art high school, studied Graphic and advertising design. I started writing poetry in my senior year, all of a sudden I realized I was discovering a secret language that seemed much more interesting than what I was doing, in comparing me going into the work force of Madison Avenue. So I decided I wanted to become a poet, more glamorous, not realizing that I wasn’t going to make any money out of it. Three years after I graduated high school, I met Andy Warhol, and he asked me to come to work for him, because he realized I had silk-screening experience and he needed someone to help him silk screen his paintings. And so what started out as a summer job, because I was in college at the time, wound up being a job for seven years.

Tell me first about how you met Andy and what your early impressions were?

"I met (Andy) through a mutual friend, a poet named Charles Henri Ford, and Charles knew of my artistic background and my skills at silk-screening, so Charles is really the catalyst that brought Andy and me together. Charles was living in New York, but he also had an atelier in Paris on the Ile St. Louis, so he was going back and forth. He lived in the Dakota, his sister lived in the Dakota, Ruth Ford, an actress, and she was married to Zachary Scott, who was a really wonderful man, whom I knew quite well. So Charles lived a charmed life."

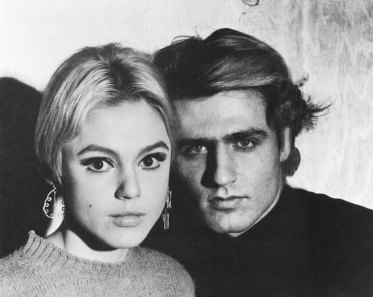

Edie and Gerard at the Silver Factory

This was before the Silver Factory?

Andy had a building he rented from the City of New York, it was a decommissioned firehouse that was empty, it was basically a shell, I don’t even think it had any electricity, and that’s where Andy was doing his silk-screening. It was three blocks from where he lived. I’d meet him at his house, and then we’d proceed to go to the firehouse to work for two, three, four hours, whatever, however long it took. We did most of the Death and Disaster paintings at the firehouse.

Gerard moving Elvis with Bob Dylan at the Silver Factory.

And we did the Ethel Scull Portrait there, we did the Tuna Fish Disaster, the Elizabeth Taylor Portraits, the Elvis Portraits, we actually did a lot of work there. At the end of the year, ’63, Andy got a letter from the City saying that they were putting the building up for auction, his lease was up and they weren’t going to renew it. So we had to find a new space, so we spent about two months looking for what I thought would be an artist’s loft; but we found this very anonymous factory space in mid-town Manhattan of all places, really away from all the artists. So he took a lease out on that, and that became the Silver Factory.

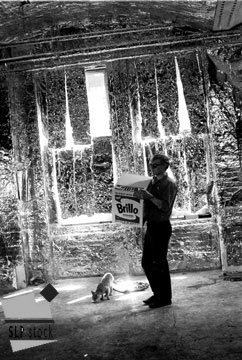

The Silver Factory.

That was the first factory wasn’t it?

No, it was not really a factory, it was just me and Andy working there, and it had no bearing or relationship to the first factory. The Silver Factory. Andy rented the fire house from the city, the buildings department, for I think, for 100 dollars, and when we come back from California early in October 1963, Andy received a notice from the buildings department saying that they were putting the building up for auction, so we had to move out by the end of the year.

I think there was a one month grace period and it was in late February that Andy signed the lease on what would become the Silver Factory, but at the time it was just Andy and me working at the fire house.

Tell me about that first trip to California.

Andy was working towards a show which we were making paintings for, at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles that it would be. It was like the early part of October. We were silk-screening a lot of Elvis Presley paintings that some were for the show, as well as Elisabeth Taylor portraits, and sometime, during maybe the end of the first week or sometime the second week of July, well just to back track for a second, I was rolling up the canvas, we were storing them in the back of the fire house on the 2nd floor and one night there was a huge leak in the ceiling and the next day we discovered that all these canvases that we had silk-screened were damaged.

Some early Liz Taylor's somehow "got away"!

So we had a new screen made and we re-silked-screened that image that was slightly different, and I was instructed to shred those damaged paintings, so I did shred some of them, but I got distracted because we were doing so many different things, that I neglected to finish that job, and now all these paintings that did not get shredded are now popping out everywhere, you know, being sold as authentic Andy Warhol !

Funny story, but tell me about the trip.

What happened was a friend of Andy , a painter named Win Chamberlain took an interest in driving cross-country which Andy was very excited about. Neither Andy nor I drive so , and then Taylor Mead, he took an interest, so Andy invited Taylor and Win and they did the driving in Win’s station wagon and Andy and I sat in the back seat, luxuriating across country. The first stop we made was in St Louis, we stayed one night in St Louis and then we drove down to the Texas panhandle, then we stopped in Albuquerque where I have a photo booth picture of the 4 of us, which is the only visual document of that trip. Then we stayed one night in Palm Beach, Palm Beach? No I am sorry, Palm Springs in California, and the next day we made our way to Los Angeles where there was a movie star party being given in our honour by Dennis Hopper .

MovieStar party in Hollywood. Dennis Hopper, Andy and admirer.

Wasn’t Andy interested in things that happened along the way on the trip? How did people react to you guys?

You know it’s just such a distant memory now. I wish I had documented it in some way but it was a very uneventful trip going and coming, it really was! Going back, it took us a little bit longer to get back to New York, but going to LA it took us only 4 days which was kind of a record, but it was very uneventful. I mean we stayed in motels, you know, it was a very anonymous kind of experience.

What kind of welcome did you get from Dennis Hopper?

It was very enthusiastic, very upbeat. I met Wallace Bourbon, who later became a friend, very talented artist, there were a lot of artsy people at the party it was really a nice affair.

And the reactions to Andy’s work ?

I would say it was pretty upbeat; it was Andy’s second show at the Ferus Gallery in LA, a year earlier he had the Campbell’s soup cans, but he did not go to that opening. But Andy was very excited about Hollywood because it was just at that time which basically anticipated the photo realist painters that Hollywood was just flooded with the most amazing billboards, they were so realistically painted and Andy was totally fascinated by that.

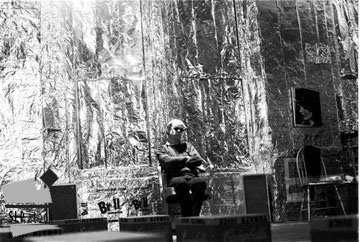

Hanging out in the Factory.

So after the trip, you all got back to New York, and I guess it was then you got the notice you had to move?

That was kind of a wake up call. So Andy and I spent about a month looking for a space; we went looking at lofts and various places in the Chelsea area and the lower east side. I was looking and I was thinking we were moving to an “Artist loft”. Andy had another idea in mind, he just wanted something really out of the ordinary, so we found the factory space on East 47th Street, such an unlikely location, but it was a big space. It had a high ceiling, but because it was a large space, the ceiling appeared to be low. It used to be a hat factory, it was an industrial kind of building with a trade elevator and Andy signed the lease for it.

Just spread out. "Mr. Loft", well before his time!

When he saw the space, did he immediately fall in love with it?

Yes , he liked it immediately , it was the space for him; it was a large enough space where he felt very much at home where he could just spread out various projects.

I think he liked the anonymity of the space. It wasn’t very appealing, it was really dank. This was before Billy came in and tin foiled and sprayed the place silver. But it was a very uninspiring space. He had a vision of its potential. It certainly was away from the art world.

We moved in about the first week in February, 1964.

At night that area was pretty much dead. The building’s no longer there, it’s a park on top of a submerged parking garage.

Billy Name's drawing of the layout of the Silver Factory.

So when he walked in and saw it, you were with him, he was in his mind sizing it, probably looking to all the corners of the room, and looking at the size?

Perhaps so, it was very minimal in terms of its functions. It had a little sink in the back, a little toilet in the back and that was it. It had electricity, it had a pay phone, or I think maybe Andy had a paid phone installed or it was there already, I am not sure.

At first there wasn't any silver around!

This is of course well before the scene started to develop?

Well the scene was developed in the tandem. I should point out that when we looked at this place, it was cavernous, it was dark it was not painted silver , it was grimy, grungy. It was a very interesting structure we encountered.

Did he sense right away how he would “decorate” it?

I do not think that Andy was really concerned about that at the time. Although we had gone to a party where we met Billy Linich (Billy Name), this was his real name at the time, and the apartment where the party was, on the lower east side…Billy was living there with some artists, I think Freddy Herko, Charles Stanley, one or two other people.

Then there was silver everywhere!

Billy had decorated this apartment and it was painted entirely in silver, the floors were silver, the walls were silver; and Andy invited Billy to come up to the factory and do the same thing, because silver for Andy represented the machine. It represented the mechanics of something . Kind of a neutral colour in a way, not being a colour, being more metallic; and so Andy invited Billy to the factory to paint the factory silver. It seemed very appropriate to have a silver factory.

Did you help on that project?

No, I didn’t

Were you there when Billy came in and started doing all this?

Yes, it was at that time that we had just started to silk-screen the series of boxes, the Campbell Soup cans, the Brillo boxes, the Mott’s apple juice box, the Heinz Catsup box, all for the show Andy was having sometime in April. So we were working non-stop at the same time Billy was spraying the factory .

Andy sits amidst a wall of silver in the Silver Factory.

It must have been Mad!

No, it was pretty neat actually. I think Billy was actually doing his work, his spray painting, and tin foiling, sort of, within. It was basically off-hours that he was doing that.

Would Andy come in and have a reaction to what had been done the night before?

Not that I know. I think that Andy approved and he liked it.

He just thought it was pretty cool?

Yes, but it certainly was different from your typical artist loft.

Tell me a little bit about, after all the silver thing happened, and the work you and Andy were was continuing, what kind of other things were going on in the factory?

Well, on the off hours, or should I say between work with Andy, I was writing poetry. I set up a little corner with my typewriter. I had a little desk next to the pay phone. So I was also writing poetry, or reading, or bringing people to the Factory for Andy to meet as potential people to be in some of the movies.

Billy was playing, he had a set up in the back where he had his turn table, and he had his little dark room, and he was playing music all the time. Mostly opera, and some of Billy’s friends would come and visit and hang out. So a lot of different things where happening but me and Andy pretty much had a work ethic where nothing would be a distraction. For us it was complementary.

What was a typical day at the Silver Factory really like?

On a typical day, I would arrive at maybe 11 o’clock in the morning maybe 10:30. Andy would arrive let’s say around noon time. Andy would read the newspaper, check his mail, and then I would have errands to do like, if I had to pick up a delivery of photographs to be made into silk screens or go downtown to pick up a silk screen, that I could carry on the subway with me; and bring it back uptown. Then we would map out whatever the painting was going to be in terms of making it and the silk screening it. Then the grunge work started by having, we had to clean the screen afterwards, otherwise it would get damaged.

Meanwhile something might be happening in another corner where Billy would be having some friends over and playing some music. Then we would have some guests. There might be a press interview, somebody from a newspaper or a magazine who would come over to do an interview with Andy. That could happen all the time, but there were various elements and activities that might be overlapping.

I f I were setting up a shot to do a scene at the Factory, I’d basically set up a dolly track (laugh) and do a “Jean Luc Goddard”, dolly around the Factory and catch all these different activities…simultaneously. You’d catch Andy and me silk-screening, you’d catch Billy Name playing opera records and talking to Ondine, and some friends seated on the couch chatting away, and maybe somebody else is in the corner drawing. I mean a lot of different things were happening.

But when Andy and were working at the firehouse, it was just Andy and me, there was nobody else.

There was no factory environment at the fire house?

Once in a while someone would visit us at the firehouse, but Andy was doing all his socializing and meeting people in the living room of his townhouse.The interesting dynamic is that when we moved into the factory, all the “business” shifted from the townhouse to the Factory, so that literally the townhouse became off limits to the media, or to even Andy’s friends for that matter.

Why do you think Andy did that?

In hindsight he realized that it was a good idea, to keep his situation very private.

So when you got to the factory, all of a sudden…?

The first thing we did when we moved into the space was Andy was having a show in April at the Stable Gallery for his BRILLO BOXES. We had to line up an assembly line and silk screen. Billy, I think that was Billy’s first documentation, he was actually photographing what that was all about, the first art project of the factory.

A lot of new people, through Billy or myself, or Andy for that matter started coming over. Everything that was involved with the media or Andy’s friends. Nobody ever went back up to 89th and Lexington Avenue anymore. The only person that was there was Julia, his mom.

Who were some of the early friends?

I brought in a lot of the poets because of my association with poetry, a lot of my poet friends like Ted Barrigan, Ron Pagent, Ronnie Tavel, who then wrote scripts for Andy’s movies. Allen Ginsberg of course. Jonas Mekas, Barbara Rubin.

When did the girls…?

The girls? (laugh) I guess I had a few girlfriends during that time. It’s not something that meant anything. It’s just the way things were.

Did the scene really start to kick in when the films...?

In ’64 we made ‘Couch’, we made sequences for ‘Kiss’, we started the “Screen Test” collaboration, those were the early silent movies. Also Andy shot the Henry Geldzahler Portrait, the summer of ’64 at the Factory. The first sound movie didn’t take place until late November of ‘64. That was called “Harlot”.

What was it like when the screen tests were going on?

Someone would come to the Factory. Andy had a Bolex. Basically Billy would set up the lights, and we’d ask this person, a friend or even a stranger, to sit down and have his or her screen test done. Basically it was just a film portrait, we called it screen test, it gave it a little more excitement, a feeling of being filmed. And you’d sit there and stare in front of the camera for three minutes. You could do anything you wanted, but basically that was the format.

Where did Andy come up with this idea?

The initial idea came up before the Factory, in December of ‘63 when we were still at the firehouse and I was looking to have a publicity still, a shot of myself to use for publicity purposes or a book, and I hit upon this idea where I would have a film of me where I would just select two or three frames and that would be the portrait. So that was basically the FIRST SCREEN TEST, in essence, and it was that idea that we decided we should do more of these, it’s kind of fun to do, and so that’s how it started.

Wasn’t there a screen test with Bob Dylan?

He just sat there in front of the camera. There wasn’t anything really exceptional about it. He’s smoking a cigarette. Barbara Rubin brought him over with his sort of sidekick roadie named Bobby Neuwirth, and Andy was thinking of the idea of getting Bob to be in a movie….Bob was a really hot item at that point already. And so Andy’s way of wooing Bob was giving him a “Double Elvis Presley” Painting.

And Bob was a bit of a punk in those days, nice, but real cocky. In the end Bob just carried this gigantic painting down the freight elevator. And I went to the window and watched them tie it to the roof of their station wagon. And they drove it back to Woodstock. Word got back at some point that Bob had traded the painting for a piece of furniture with his manager, Al Grossman.

So Bob, in essence, really didn’t take Andy that seriously, and he ended up not being in any major film of Andy’s. I don’t think they really liked each other. I think basically what happened, I think Bob found Andy to be pretentious, because Andy was behaving peculiarly. Maybe Bob felt a bit put off by that, he couldn’t take Andy seriously.

Was the Silver Factory, like always crazy?

Some days the Factory would be very quiet, where nothing was really happening. Billy would still be playing opera records but no one would come by. People have this impression there was an on-going party at the Factory, which is really not the case. It’s interesting how with time a myth gets built up about a situation that people never really witnesses; and, in point of fact, the Factory was a daily routine that kept on changing within its routines.

What is exactly a “party”? When you enter…

Well, you take a freight elevator to the fourth floor. It had a gate that you would open, it was a real old-fashioned freight elevator. Then you’d open this big door that had a little window on it, and you’d enter this big silver palace. (laughs) “Tin Foil Palace”, is what I would call it, and then you’d have to try find Andy in the midst of all that. I mean there was no real, it wasn’t an office situation, the way the later Union Square Factory was, where there were desks and telephones and stuff like that. We had a pay phone at the Silver Factory. When we had to make a phone call, we had to put a dime into the phone.

And when you entered, what were people doing?

In a party situation, people are milling about, talking. Billy’s playing records. It was not like what you’d really call a party situation, it was more of a social situation. The dynamic was more socially oriented, with two or three people here, two or three people sitting on the couch, people doing different things. If you see my movie called ‘The Film Notebooks’ there’s a whole sequence…an encapsulated version of what it looked like at the Factory, when Salvador Dali visited.

Was that the great party, where Salvador Dali…..?

I wouldn’t call it a party, but there were a number of people when Dali made that visit, and Andy and I did Ultra Violet’s screen test. We also did a screen test of me that day, and a screen test of Dali, and Billy Name’s screen test was done that day too.

As my understanding is that yourself and Billy were there first with Andy. Was there another person there with you guys at that point?

Well back in, I think, it was the summer of 65, Andy was introduced to a young filmmaker that was working with the Masel brothers, and his name was his name is Danny Williams. Danny at some point was at the Silver Factory and he was there for about a year. He set up his own little area, and he primarily, his function ultimately was that he was designing the lighting for the performances we were doing with the Velvet Underground.

Tell me a bit more about Ondine, was Ondine around at this point?

Ondine was around. I met Ondine through Billy, actually I met Ondine through John M. at a loft party prior to meeting Andy. Then I was reintroduced to Ondine at the Factory through Billy. So Ondine would come and go from time to time, and then I would hang out with Billy or Ondine and his crew . Friday nights would come and we would go on these all night Binges, and I created a name for what we were doing. It was called “the dawn patrol”, and I would write poetry about it. I fount that I could be very romantic in my own naïve state.

You say you were still naive, but tell me about the dawn patrol.

The dawn patrol, we would start at someone’s apartment , you know playing records, hanging out. There was probably a little amphetamine going around . We did, I mean, I ended up writing poetry all night long. We would get into little groups, we would get into conversations with each other. Maybe there would be some entertainment, you know, and then we would end up going out in the morning looking for a luncheonette to be open, and at that point it would be “ the dawn patrol”.

And you guys were all pretty young and you could go for 24 hours without really collapsing.

Yes I was in my early 20’s, the other guys were a bit older than me, a few years older than me, I was probably the youngest in the group.

As this was sort of evolving, tell me about some of the more interesting people that in your opinion started to filter into the factory.

Well there was someone who became a friend of mine names Dennis D. who ultimately lived and died in Paris, and he did not spend much time in the Factory, but he was there every once in a while, and he had lot of good connections, he knew a lot of very interesting people.

Was there this huge influence that the all beat generation guys had on what eventually evolved into the Silver Factory?

Well I am not so certain that there was a connection. I would have to debate that a little bit. I mean Andy was fascinated with poetry. I mean I had brought Andy to a number of readings at a café in the east village called Café Metro where they would have open mike readings on Monday night and solo readings on Wednesday nights. So Andy came to a number of those readings and that is when I introduced him to Ronnie Tavel who later became a screenplay writer for Andy’s sound movies. So there was a lot of enthusiasm in terms of Andy meeting people that would be very helpful towards his goals and his ideas . Andy was very aware of what was going on. The Opera. Also there was an impact coming from the Judson Dance Theatre. We would go to concerts. There was a lot of artistic activity going on at the same time in terms of what we were doing.

When you started working with Andy, was he was already fairly well known?

Well, when I started working for Andy, I really didn’t know who Andy was. I don’t even know if Andy knew who he was at the time. He was not really popular. The pop art movement was just getting on the runway when I started working for Andy. The pop art movement in America started around 1962 but even then by the time I started working for Andy he was just getting notoriety . The artists in that group, in that convergence, were just beginning to get notoriety in the press. It was only after working with Andy on that first day, and going back to his house, and Julia his mum made lunch for me, and she was so happy to meet me, and she thought of me as Andy’s little brother, and there happened to be some canned soup objects or things that were referenced to Andy and all of a sudden I realised that I had seen illustrations of this in Show Magazine, so all of a sudden it dawned on me that Andy was part of this pop art movement.

In terms of that particular period Andy had already accumulated a degree of wealth at this point in his career.

Oh yes yes, but it was a different career. Andy became a very successful commercial art illustrator on Madison Avenue. He specialised, he was working (doing illustrations) for I Miller Shoes. That is where he got is notoriety, and I mean he was getting lucrative accounts, contracts, a lot of freelance work. So he was, you know back in the late 50’s 1960, 61, I mean the value of money was different. So Andy became a very wealthy person, so he was able to buy his house, on 89th Street and Madison Avenue .

But there was something that was very unsatisfying about what, what I think Andy was feeling about what he was doing. He wanted to reach more than what he was doing in terms of his work and of course, he was already attracted to the art world and Andy was basically in a position to buy his way into the art world. One of the ways he would do it was to go to the art galleries and buy artwork. And of course the gallery owners, if they knew Andy was going to show up for an opening, they were already anticipating a sale. You know, like Andy even commissioned portraits, and paid a fortune, of himself and his boyfriend. So Andy, in that way, started accumulating art. Also it was Andy’s introduction to the art world; it was his way of buying his way into the art world.

So in your opinion it was clearly a strategy on his part?

Oh very much a strategy, it was very much a strategy it was a plan. I don’t think it was, you know an obsession, but certainly there was a strategy there.

So by the time he got to the factory stage he had pretty much given up the commercial side of the business?

No, not true, Andy was still getting freelance work, but he would turn that work over to a man whom I met very early on when I was working with Andy named Nathan Gluck, and Nathan would basically do the art work for Andy under Andy’s signature.

So it was almost another side of the Factory to keep the old business kind of alive as you moved into new business?

Well Andy was very clever, because he realised that he was not going to be making money right away on what he was doing, so he needed to hold on to those old accounts, so it was very smart what he was doing. So he would get an assignment, Nathan would be there at the house, at the drawing board, and he would be doing illustrating, and rubber stamping, and blotting, and whatever. He knew Andy’s style inside and out, and that work would eventually get bought and published or whatever.

Under Warhol signature?

Yeah, which seriously was Julia’s handwriting . Andy had one time given me a “Lettra-set”, you know what “Lettra-sets” were in those days? You would and buy a sheet of any number of type- faces, and actually Andy had a “Lettra-set made of his mums handwriting, and I used it for an announcement I did of a poetry reading that I did at the Costello Gallery in 64.

As this was going on, as the factory era was beginning, as the art stared to be creative, was Andy enthusiastic about what he was doing? Did Andy believe in what he was doing?

Andy had a certain faith, and we would try certain things with the silk-screening. There was a lot of exchange and input. I introduced Andy to “superpositions” with the Elvis paintings back in 63,and 64. It was always like let’s try this; and basically if we made a mistake, Andy accepted it. We embraced the mistakes as it were, we had a work ethic, we just, if we had a new idea for a painting we would go and get a silk screen made and see what it would turn out to be.

Did he at any point, did you sense that at any point, that he was disappointed with the work, with the direction of the work?

No. No, not at all. Andy was very optimistic. There was never a moment where I thought Andy was pessimistic about anything he was doing.

Did he ever get shook with the idea that maybe he was moving on the wrong direction?

No, he was a boy in terms of being carried along with the media giving him the attention, the acknowledgment the recognition , Andy was never really pessimistic about what he was doing.

As the art started to really move, as you guys were really, excuse the term, cranking it out, a lot of other things were starting to happen in the Silver Factory, can you tell me about those other things?

Andy also became interested in making films, and it was actually in summer, late spring, no summer; it was in July of ‘63 that Charles Henri Ford and I took Andy to a wonderful camera store, which sadly no longer exists, called Peerless Camera , which was across the street from Grand Central Station; and it was a big store with two entrances on 43rd to 44th Street. And that is where we had Andy buy a Bollex camera with a motor drive, which made it all very easy so he would not have to crank the camera, whatever. He would just have to press the button .

The first film he shot was a film of a friend of his, a former boyfriend of his sleeping. So Andy had the keys to the man’s apartment, and we would go there, and the camera would always be there with the tripod . His friend liked to sleep. He could never really wake up, so he was an easy subject to film, and the idea was to film his friend for 8 hours. Ultimately Andy shot only about 6 hours and then we dupped a lot of the three-minute reels to get the 8 hours of sleep which was the regimented time, the normal time for someone to sleep.

So what was a typical day for Gerard at the Silver Factory?

It started late morning, probably, the earliest would be 10:30, maybe 11:00. And I would call Andy ahead of time in case he needed something to be picked up, whether we needed to get a silk screen , pick up a silk screen at the silk screen company down on Canal and Broadway, schlepp that up to the subway, if it was small enough, bring it to the Factory on 47th st., or maybe I would have to pick up art supplies or cans of paint, whatever, kind of like a drudgery situation, but things that we needed to do our work for that day, or that week.

So we would prep up before doing a painting that day. I’d prepare the painting if I had to do a kind of stencil, use masking tape to separate an area that needed to be hand-painted, and Andy or myself, I would do that. If it was a big canvas, then Andy and I would silk screen the canvas together. And then I would clean the screen. So usually we used black ink silk-screening, because all the other areas were hand painted in color. And then the thing would have to dry, so that pretty much took care of a good part of the day, usually in the afternoon. Then, there would be, if we were making a movie, I’d help Andy carry the equipment, put up the equipment, whether we were doing it at the factory or someone’s apartment. And I would deliver the raw stock to the film lab and pick it up, and get a print made and pick that up, that was pretty much the routine. And then it was Party Time.

Why do you think that Andy got interested in making films?

Certainly from the visual aspect, the idea of a static image taking on a moving image, it was just another appendage to what he was doing with the paintings. Andy throughout his art was always involved with photography . There was a critic who actually wrote a text about my own work where he referred to Andy and I as having been proto-photographers. Very much we had a photographic vision. Long before we picked up a still camera even. So a good example of that would have been Andy making a film of all the paintings that we made, basically paintings of photographs and the silk-screen process was another appendance to the photography we did.

What about the idea that Andy liked the idea of film because he liked the idea of Hollywood and he wanted to sort of create his own Hollywood?

Well, Andy created his own Hollywood based in part on having been rejected by Hollywood.

You said that Hollywood rejected him, was there a real, clear reason why they rejected him?

It was just a matter, somehow he wanted to be taken seriously by the Hollywood that shut its doors on Andy , so Andy kept on making movies anyway until the end of the 60’s and then Andy pretty much fizzled out after that. I think the last major movie Andy really made for himself was a movie called “Blue Movie” . But like in the artwork where Andy was kind of imitating the history of art, like we are going to make flower paintings, self portraits, those sort of traditional images in the art world, in the history of art that is, the same thing happened with making the movies . We started out with making silent movies with the Bollex, and then we graduated to sound movies with the Arkin camera which Andy bought, then we went from black and white to colour. It kind of followed the history of movies , the pattern you know. I think probably because they really did not understand, Hollywood had its own set up, its own system, its own vocabulary and Andy’s vocabulary was totally incomprehensible to what they were doing so they saw no use in terms of connecting with Andy at that time.

In your opinion did he have any contacts in Hollywood, did he try to source, to create something?

Not to my knowledge, there may been some nibbles, some initial interest but it but it never really went anywhere.

Let’s talk a little more about the film thing, it’s clear and so clever how Andy would look at his art, and create his art based on his photographic idea. Moving into film, why did he pick the subjects he did?

Well first of all we have to take in context the different periods in Andy’s film making . I think that Andy’s most conceptual period would be when he was shooting with the Bollex, because he did not have the apparatus for the sound, and basically he was not even thinking of shooting in colour. And he only had 3 minutes to shoot on a roll of film. So as Robert C. once said, “Content is the extension of fog in poetry.”, and the same thing applies to Andy in film. To give you an example there is a film called “Eat” of his friend the artist Bob Indiana eating an apple for 30 or 45 minutes. Andy shot that in 3 minute segments with his Bollex. I mean that he had to change the film every 3 minutes . He had the motor drive attached to the camera so that he could shoot 3 minutes without cranking without rewinding. So he could shoot 3 minutes from beginning to end, then he would have to change the film, and that went on for like 30 or 45 minutes, and that was the concept of that film. One to one ratio kind of shooting . Andy was understanding the nature of film as he was shooting more film. A good example of that would be in the summer of ’64. We rented an Auricon camera to shoot “Empire”, so now we were shooting 1200 foot reels but without sound, but using a sound camera. So that was on a weekend, so we didn’t have to return the camera until Monday. So we had 2 rolls left, and we had Henry G. coming to the factory and we did a portrait if Henry smoking a cigar for 70 minutes.

Then we shot our first sound movie in December ‘64, at the Silver Factory called “Harlot”, but basically the set up was a table. I was in the film. Mario Montes is a star. She played a Jean Harlow character in drag; and a boyfriends of Andy’s was also in the film called Fabien and a girlfriend of a film critic at the Newsweek magazine was in the film, and we were sitting behind, Philippe and I were sitting behind Mario and Carol who were sitting on the couch. There was no sound, I mean Andy was shooting sound but there was no sound. There was voice-over. Two poets were talking about what was going on in the frame of the picture, but they were off camera and out of the frame. So you are looking at a voice-over movie for almost over 70 minutes, and only at one point towards the end of the second reel do you realise that actual sound is being recorded in the film, it’s when Philippe throws a beer can and the bear can lands off camera on the floor and you hear it crash and you suddenly realise that this is a sync-sound movie. But you do not see anyone talking.

So in essence this film took Andy to the next stage which was, trying to, in what we call in traditional film making, he’s making a story wasn’t he? With the early films……

No , the early films are conceptual films, “Haircut”, “Eat”, “Sleep”. Andy’s early sound movies were all static movies, the camera didn’t move, the zoom lens didn’t move, they were basically staged tableaus in a sense. And of course after “Harlot” was made, that was around the time that Andy met Ronnie Tavel, and Andy though we needed to start having scripts for his movies. Then we had “Horse”, we had “Vinyl”, we had “Poor Little Rich Girl”. T hen a number of Ronnie Tavel scripted movies, “ The Lives of Juanita Castro” . Another great film that was made in ‘65 , was called “Camp” which was an idea I came up with which was to have a child watching a TV show on Sunday morning called the children’s hour which was basically a talent scout kind of show, so “Camp” was actually a parody of that TV show. I was the MC and then everybody did their thing, amazing stuff was going on .

Tell me about the Superstar thing.

Well Andy actually invented the term. There was no such thing as superstar, but the idea of the word “superstar” was that our stars were not just Hollywood stars, they would bigger than Hollywood stars. They were superstars, you see, so the emphasis, so the underlying would be on the Super.

And this kind of went along with this idea of like the old days of Hollywood? I think that in Andy’s mind he felt that, he wanted to have that noble feeling, where he would have his entourages of actors, and writers and the all bit players and the superstars.

Well, the superstar idea evolved out of that, and actually Andy’s repertory of actors, or real people that is, initially came from Jack Smith’s studio. But Jack Smith, you know, the lobster studio, whatever, if you want to call it the Jack’s “Flaming Creatures”, “Normal Love”, and that included Maria Montes of course and number of other creatures of Jack’s. When Andy shot that in Dracula, basically it was a Jack Smith movie, even though Andy was behind the camera. So I think Jack was a major influence on Andy’s filmmaking at the time, In terms of the people that were being used.

Let me ask you a question about Jonas Mekas. Did, Jonas Mikas have anything to do with Andy’s films?

Well Jonas was a great promoter of underground movies, of the quote, unquote “New American Cinema”. And certainly Andy fit into that vision of what Jonas was trying to promote, and he edited a magazine called “Film Culture” and every other week they would give these special awards to a film maker. I believe that in 1965, Andy received the Film Culture award, you know, so Jonas was an early promoter of Andy’s movies

Let’s go back to the Superstars for a minute, tell me your impressions of some of Andy’s superstars.

Well, they were all real people, as it were. None of them were real actors, none of us studied acting, I mean I never really considered myself an actor even though I was in some of the movies.

Certainly one of the great superstars of Andy’s movies was Marie Menken who was a film maker in her own right. There was Ondine of course, who was just wonderful spontaneity, I mean that tour de force scene in “Chelsea Girls” was just an amazing piece of film making, it’s still shocking in some ways.

Of course one of the greats of all times who is luckily still with us, was Taylor Mead who will always be, you know, respected and admired for who he is and what he has done in acting. Taylor was more of, was initially more of a trained actor but totally out of the ordinary. I would put those three on the top. Marie Meken, Ondine and Taylor Mead.

What about the girls like, Edie and Ultraviolet, were they important?

I think I would place the emphasis more on Edie Sedgwick who was Andy’s first real discovery, and probably still his greatest discovery in terms of the kind star personality, and that was the closest probably Andy would come to Hollywood in a sense; the period when he was making the films with Edie Sedgwick

How did he discover Edie?

We were at a party at a film producer’s house, a man called Lester Persky, a very wonderful, warm hearted person, misunderstood a little bit, some people may be put of by Lester because he was kind of a loud person, but he was a full of laughs and he had a warm heart. He was close to Tennnesee Williams, and that is where I met Tennesee, and that is where we met Edie Sedgwick.

How did she get there?

Through one connection or another, she was there with one friend of hers, Chuck Wein, who basically was the man behind the scenes in terms of delineating a kind of make up script for

“Poor Little Rich Girl”. That film was made just after we made Vinyl, and what happened was, interesting, this is when Andy embraced mistakes. We shot the film, two reels, brought it to the lab, picked it up, brought it back to the Factory, screened it, and then we discovered that there was an element floating around in the lens, meaning we were out of focus. So we shot the film again, a few days later, in Edie’s apartment. We got things set up, got it in focus this time, and then Andy decided that we were gonna open the film with the first real that was out of focus and close it with the second reel that was in focus. So it was an interesting concept, do you think that Hollywood would accept an out of focus movie? There was your unorthodox vocabulary.

Tell me, what do you think were Andy’s first reactions towards Edie

Well first of all, Andy was a real social climber. Right away he already new that Edie came from a wealthy background, and tradition, and good name, and good breading. And Andy was very impressed of course, “Oh come to the Factory let’s make a movie!”, you know, and Edie was very open to that, cause she had just arrived in New York a few weeks or a couple of months earlier, and she was looking to do something with her life. She was interested in painting and she did a little bit of painting, but Edie didn’t really have a focus, she was living at Jean Stein’s apartment at one point. I mean, she just needed a grounding, she needed an anchor, and so this is a ideal situation, it was “bees to the honey”, you know, or bears for the honey, so it was a very eventful meeting . Edie Sedgwick was Andy’s first real discovery and probably still his greatest discovery in terms of the kind start personality, and that was the closest probably Andy would come to Hollywood in a sense, the period when he was making the films with Edie Sedgwick.

Was Andy like a father figure to her?

I really wouldn’t characterize Andy as being a father to her. I would say more of a confidant. I mean Chuck Wein was definitely a confidant to Edie. Andy was more on the level of a friend, supporter, companion. They went to a lot of parties together, you know, and we did a lot of things together. We went to Paris together, Chuck, me, Edie, Andy. Andy paid for our plane tickets, you know, we stayed in the best hotel on the Seine. Andy had a big show of the Flower paintings. I gave a poetry reading at Sonnabend Gallery, it was an eventful 2 weeks.

Tell me more about the trip, some of the things that happened.

I know the first night we arrived in Paris, we went to Cristal’s, which is a club, a disco, as they called them in those days, and that is where we met a friend of Edie’s that later became a very, very close friend of mine named Rosie Blake who was living in Paris, so it was a wonderful exciting period in Paris, I mean I was just a kid from the Bronx and here I am socialising with all these rich people, and glamorous people. I started writing fashion poems about models getting killed in car crashes and things like that, so it was a very inspiring a very momentous time.

Sounds like it was probably the first time Andy had the chance to be close to Edie in the sense that she is really “inside”. Did Andy love Edie do you think? Did he have a crush on Edie?

No, I don’t think so; the emotions were not that dynamic. Different kind of dynamics of what was happening; Andy perhaps thought that Edie was his ticket to Hollywood.

So he kind of looked at her as a real opportunity to get back to Hollywood, and say, “Hey boys look at what I got”.

Well it was not getting back to Hollywood. There was still that forward momentum. He had not been fully rejected yet, we are talking early on here; but I think what happened to Edie Sedgwick and Andy was based on opportunity to a certain extent. I do not mean that in a crass way, I mean that in a kind of enthusiastic way. And Edie in her naïve way, she saw Andy as being her ticket to Hollywood, but she didn’t really understand what was going on. I think at some point Edie failed Andy and Andy failed Edie and that is when Edie walked out, and she basically walked out on Andy.

Because at some point, what happened was, I mean Edie was (‘broke’) when we met her. She was already at the end of going through her second trust fund, so she had been put on a side allowance, of like $1000 a month, which probably went a long way in those days. And Andy was financing the movies with the sale of his art and with the advertising jobs he was still getting.

I mean the movies were not making money so Andy was not paying anyone to be in them. It was basically volunteer work in a sense and sheer enthusiasm. But somewhere along the line, I believe Edie was misinformed and also ill advised by outsiders, who said, “Hey, look at these Andy Warhol movies, he is a rich guy, he should be paying you!”. And so the bug was planted, the seed was planted and I remember it was Christmas week of 1965, and we were all having dinner at, forget the name of this restaurant, it was on the west side near the Lincoln centre, it was a hamburger joint, but an upscale hamburger joint. Paul Morrissey was there and then some (people) from Velvet Underground were there and I was there. At that point she, was already being wooed by the Bob Dylan camp which included Alain Grossman and Bobby Newirth. Not so much Bob Dylan, that is kind of a misnomer, and basically she just “split her teddy”, you know, “When are we all going to see some money from this movies?”.

At that point her allowance had been reduced to $500 a month which was just about enough to pay her rent. She still had her charges covered by her father at certain restaurants, she could just sign the check and send the bill off to dad and she still had her Mercedes, and Andy, you know, just held tight, “I do not have any money, I can’t pay you.”,

“I can’t pay you.”, he said. He was trying to convince Edie, and at that point, he was getting very nervous, “At some point we all going to get rich you know.”. Edie just could not wait around any longer and she literally physically left the restaurant.

She made a phone call, came back, and said “I am leaving.”. Probably she called somebody in the Bob Dylan camp, and so she was gone. So Andy disappointed Edie, and Edie disappointed Andy. It was a, you know, a sad situation.

And then Bod Dylan didn’t have anything to do with Edie?

Not at all. I think that Edie was under the impression that her ticket to success now laid with Bob Dylan. But Edie did not have innate talents. She hadn’t studied acting, she had a terrible singing voice, and she thought that she was going to be singing duets with Bob Dylan , and ultimately she ended up not doing anything with Bob Dylan ,that just did not happen.

Well this was a big crush for Andy I am sure, how did he bounce back from that?

At that point we were just starting to work with the Velvet Underground, and Edie was my first dancing partner, but Edie did not want to be a go-go dancer. That was not her image of herself, but she did it, and we danced together at this, we were hired to play at this annual psychiatrist convention at the Delmonico Hotel in New York, with this big ballroom. And there was Jonas Mekas. He got it documented in his notebook footage. You have Edie and me on stage dancing and the Velvets behind us performing, and Barbara Rubin did a total assault on the psychiatrist convention by pointing the camera, a bollex camera, right up into the faces of these people. But Edie did not see herself (doing this), I mean Andy thought that we could do something with Edie and the Velvet Underground, but there was really no place for Edie on a high scale within that complexity, there was just nothing for her to do. So, you know, she pulled up stakes.

And with Andy being crushed about this whole thing; he had to react in a way where he would go, “Oh my God, who will be my next superstar?”?

Well, at that point we had Ingrid Superstar who was a very sweet girl, terribly misunderstood, made fun of, joked at, whatever, but a very sincere good hearted person, who thought of herself as a Superstar. Chuck Wein brought her to the Factory. She thought she was going to be the next Edie Sedgwick. No way could that ever happen, but she was still great in her own way in the movies, she was like, she was like the Eve Harton of the underground movies, of Andy’s movies she was the Eve Harton, she had this wonderful kind of dippy, dippsy, character that kind of victimised herself in a way. Especially in “Chelsea Girls”, but I don’t think that Andy was completely satisfied with Ingrid, you know. He was also, we were very much involved with the Velvet Underground at that point, so Andy had something to fall back on.

At that point Andy’s art was still moving. Did he change at that point because of the drama of Edie?

No Andy pretty much kept at it. We had a work ethic that I mentioned earlier, so Andy pretty much kept it a separate situation. The interesting irony, if we look back at this now, in terms of our discussion, is that you want to ask yourself why didn’t Andy ever make a portrait of Edie? He never did. Very interesting. We had all the photo booth “Ready-Mades”, of course, but it’s not really the same thing. I think Andy had planned to do one of Edie, but ultimately never got to do it for some reason.

Did Andy do portraits of any of the other superstars?

No, not at all. I think that it just never really dawned on Andy to tap into that vast roll of material that existed. I do not know why; I mean once the idea maybe, and when Andy and I started the silk-screen, screen test collaboration which was an official collaboration, we were thinking maybe we could make some portraits, some painting portraits, or rather Andy would make some painting portraits from the 4 by 5 negatives that I would select from the film frames. But then Andy got side tracked and we never pursued that .

At that point in time to support the movie making at the Factory Andy was doing a lot of commission portraits, right?

No he wasn’t, he was doing very few. In fact, the last painting Andy and I made together was a commissioned portrait back in ‘68 of Dominique de Menil, and she had number, he made a number of portraits which she bought, and they weren’t from a photograph that Andy took. At that point he was still working from other people’s photographs; and as you know he got in trouble for with the Flower Paintings. But for the Dominique portrait, she had given Andy a photograph that a friend of hers took, and that was the last commissioned portrait that I worked on with Andy; and she bought a number of these to give as gifts to her children. Now earlier than that, there was a commission portrait, again based from an official photograph from the files of this life insurance company at in Omaha somewhere, the portrait of an executive who had died and this was a memorial portrait it was it called “The Anonymous Man” or something like that.

The point I was getting at here is that he has all of this talent, all of these beautiful women, people around him, that could be subject matter for the art side of the business, yet for some reason he did not see that as having a potential. Why?

Well I think that I can pinpoint it a little bit. First of all Andy was very much involved in other subject matters for his art, so he was not thinking along the lines of tapping into this area.

He was doing self-portraits back in ’66, well ‘67, and at the end of ’67, he had, I was not there at the time I was living in Rome, but he had to move the Factory to Union Square, so that was a distraction for at least a couple of months, and then he was out in California filming “San Diego Surf”. So there were a number of distractions and also maybe Andy was not ready psychologically ready, or he didn’t artistically recognise the potential to start doing a lot of commission portraits. That really didn’t happen until after I left the factory. That happened in early 70’s through Fred Hughes, so Fred Hughes was really behind generating that kind of income, Andy started really making real money.

Who was Barbara Rubin?

My friend, a film maker. Barbara Rubin, was basically a very strong intellectual force on Andy in terms of her spontaneity, her way to recognise spontaneity. Andy was very open to ideas, particularly when Barbara was there. She had an abundance of ideas, and Andy was always listening to her about certain things..the things that she had in mind to do were really good ideas, and he went along with that.

She was a catalyst that just brought a lot of really interesting people to the Factory. Bob Dylan, and Allen Ginsberg, Jonas Mekas , Donovan and the whole concept of the Uptight series with the Velvet Underground. She was a very spontaneous person, very intellectual minded, and very convincing…..

How did the Velvet Underground thing happened?

One day Barbara approached me and says, “I want you to come down with me and see this group I discovered.”. I said ok, so Barbara and I went to this café in Greenwich village called the Café Bizarre, and there was this group called the Velvet Underground. It was late afternoon, there were some young people sitting at tables on the side of this open space in the back of the café, there was no stage to speak of, it was level like this, and the group, it was four people, there was John Cale, Marie Tucker, Lou Reed and Stirling Morrison. At that time, I had a whip which I had bought , I wasn’t even thinking S&M. I didn’t even know what S&M was in those days. I bought the whip as a fashion , you know, appendage, you know like a piece of clothing as a decoration. I’d tie it to my belt. I bought it in a weird shop in the West 40’s near Time Square that sold umbrellas and whips and, I don’t know, luggage. So I had this whip, and we went down to hear this group play, and Barbara encouraged me to get up to dance and I was all shy at first. I was sitting right in front of the group, I don’t want to block the group, you know, but she said, “It’s ok, they like that!”, you know; so I got up, and I started dancing; and at some point, I unfastened my whip, and I started dancing with the whip on the floor, not even knowing what their songs or what their music was about. And eventually, by my getting up, I encouraged some of the people who were sitting down, and they started getting up and dancing also. So at the intermission I was introduced to the group, and they said, “Oh, you know, I was kind of apologising to them, I hope I wasn’t in the way or whatever, and they said, “Oh we loved it, oh please you have to come back and do more dancing!”. So it was a very exciting moment for me and then, a couple of days later, a few days later, Barbara and I brought Andy down, and at that point we were with a larger group that included Nico and Paul Morrissey and this music critic from the New York Post that was in Woodstock. So it was a larger group of us, and Andy was very excited by hearing the Velvets, and he invited them to come to the Factory and use the Factory space to rehearse.

So that was a wonderful thing that happened, you know, and that was all due to Barbara; and at that point, Andy was planning, or rather Jonas Mekas had approached Andy about doing a retrospective of the Stones at the Cinemateque, and so Andy got the idea of an Edie Sedgwick retrospective. I think this is the beginning of the end of Andy’s relationship with Edie.

What happened was the dynamic changed and now Andy was thinking, wouldn’t be nice to have the Velvets performing in front of the Edie Sedgwick movies at the Cinemateque. Well Edie was not having any of this, I mean she was really upset about this, you know, perhaps rightly so at the time. I mean she didn’t really see the dynamic in all this, it certainly it would have been a distraction to what she was doing on the screen and in actuality, it wouldn’t just include her movies. Andy was going to include other films behind the Velvets including Vinyl, which we ultimately used for a lot of the performances. We did this multimedia program at the Cinematheque for I think 2 or 3 nights and it was a big hit actually. A lot of people came, and of course at that point, I was dancing. I had choreographed some of the pieces that would go with the songs, so it was kind of a very integrated affair.

Why do you think turned Andy on about the idea of the Velvet Underground?

Well Andy liked, Andy was pretty much into dimensions in a sense and layering and this is just another artistic aspect or another dimension to what he was doing with his art. Now he had live art, you know. Maybe Andy saw himself as a music promoter, maybe this was another way of you know, gaining the attention of Hollywood.

Well, let’s face it, he wasn’t making any money on his movies to speak of?

No

He was using the art to finance him movies, now all of a sudden he has this idea to throw music into this?

Right, perhaps he thought there was certainly money to be had in the music world. There was a point after we made the Flower Paintings, that Andy made some kind of official, unofficial announcement that he was giving up art, so that may have happened actually when the Velvets came into the picture. I am not sure of the chronology now, but Andy was still doing the art, so it was kind of a strange mix, sort of a paradox.

Who was Andy’s favorite performer in the Velvets?

Well he liked Lou Reed a lot and he was very encouraging towards Lou Reed, giving Lou Reed more of a boost in the work ethic. You know, write more songs and then he wanted…see the thing about the Velvets, Ok, is that with all the intensity of music and the songs, there was no charisma in the group. That was the one thing that the group was lacking, and also they liked playing in the dark, they liked playing with their backs to the audience, they liked throwing the guitars against the sound system, creating the feedback sound. I mean the Velvets really introduced that idea, but there was, the only person that had charisma in the group at that time was John Cale, you know, and then Kenneth Lane gave us jewellery to wear, you know, and John Cale had a snake necklace and stuff like that.

But even with all that, Andy said, Andy thought right away, let’s put Nico in the group. At first the group was very resistant to that, and then ultimately they wrote 2 or 3 songs for Nico to sing.

When Nico would sing with the group, she would sing her Bob Dylan song that she had cut a 45 of in London. The Velvets hated playing that song, because it wasn’t one of their songs, which was understandable, so finally Andy encouraged Lou to write 2 or 3 songs for Nico, so the Velvets would feel more comfortable playing their own material, so that’s how that happened.

How did Nico get involved?

We (Andy, myself and some others) went back to France in April or May of 67 to the Cannes Film Festival. We also went to London, and that’s where I met Nico, through a friend of mine who was living in Paris, Dennis Degan. So I told her if she had plans to come to New York to call me at the Factory, which she did do, shortly before we all met the VELVETS…..

So you were responsible for bringing in Nico to the Silver Factory?

Well, there was a lot of talent out there that could be utilized in terms of just being helpful, or being creative, helpful to Andy’s work.

There was some relationships going on with Nico weren’t there?

There was, I believe John Cale and Lou had small relationships with Nico at one point. Like she was being thrown back and forth.

And is it true that Andy had a bit of a crush on Lou Reed?

It’s possible, I am not privy to that.

Ultimatly with Lou, there was again something else that had to do with money. It had to do who I am (Lou), as an artist going with Andy Warhol, not in line with what, with Edie from what I can tell, can you talk about it?

I am little on the outside of what happened at that time, but I believe that what happened was Lou had bigger ambitions. OK, he didn’t…he saw the group getting type cast, in you know, he and the group were basically under the Andy Warhol spotlight. He had bigger ideas for the group and more ambitions, and wanted to go in other directions. What they were I am not sure, and at some point, and definitely they had already brought out 2 albums, both of them produced by Andy. Andy didn’t make a nickel on any of those albums, Andy didn’t see a penny, who saw the money I have no idea, maybe just the record company, maybe they were just bad deals, maybe Lou, because Lou is very educated about the music world, he cut records when he was a teenager, so he new the ins and outs of the music world, so maybe he felt dissatisfied with what was happening, with Andy not being a good business man, not wanting to be typecast and at some point he actually fired Andy as the manager of the group.And so there was a split there, so I think that Andy went back to doing, making some art, some self portraits and stuff, they basically had it out, and by the spring of ‘67 it was pretty much over. I think the second album, actually the second album came out a little later. I think it came out in 68, but it was already in the can, as it were.

Can you tell me about The Exploding Plastic Inevitable?

W hat became known as the EXPLODING PLASTIC INEVITABLE started developing into a full fledged multi-media show, which we then took on the road. We did something in New York for the annual Psychiatrist’s Convention….That was before we used the title “Exploding Plastic Inevitable”. Barbara Rubin had come up with the name UPTIGHT which I later adopted for the book on the Velvets. It was a real anarchistic total assault on the audience. It started out being called Uptight actually, because after the Psychiatrist’s Convention we played the FILMMAKER’S CINEMATHEQUE which at that time was in the basement of the Wurlitzer building on 42nd. St. They had an auditorium in the basement that was used to test their equipment, and Jonas had taken it over as his journeyman’s Cinematheque. The whole ides was that Barbara with a Bolex would be running up and down the aisles, basically in your face with the camera, and asking weird questions like, do you have sex or do you love, weird questions just to get people quote unquote, ‘Uptight’. Then the music would start.

How did the audience react?

They were surprised or anxious or whatever. I think Barbara picked that up from, I guess she was reading about ‘Anarchistic Theatre’, or she had connections to the Living Theatre even. A certain kind of philosophy behind what she was doing, and it sort of lent itself to the music which was very, in an assertive kind of way, it was very assaulting.

Somehow we ended up being hired by somebody who had heard about us. So, officially that was basically the first public performance. We had two or three other gigs, the DOM on ST. MARK’S PLACE for maybe two or three weeks. And then we got hired to do a gig at THE TRIP in Los Angeles, which then led us to do weekend performances at the Filmore.

The format of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable would start out by showing a Warhol movie. And I think before the film was even finished, the band would start setting up while the movie is being projected behind them. Then they would start playing and I would come on with a dancing partner, which at that time was MARY WORONOV. We, the Velvets would play the music, and I would go through all my routines, which I had pretty much mapped out for each song. I was very energetic in those days, I loved dancing.

It was very visual. The group themselves were not very visually oriented, I mean they all wore kind of drab looking clothes except for JOHN CALE, and NICO of course who wore white suits, pantsuits, and stuff like that. She looked good. It was very visual because you had the films, and you had slide projections, not gels, Paul Morrissey would design these slides that would be projected onto the movie, so it was a kind of a multi-layered experience. Even in its very primitive state it had a sophisticated look to it. And very improvised, spontaneous, and all that visual stuff kept piling up as the band was playing.

(Mary and I) We’re actually in the center. We’re going back and forth from left to right to center. We actually had almost the entire stage to play around with. People were very curious about what we were doing. They had no idea, It wasn’t just some rock band playing on stage.

Did they really understand the connection to Warhol?

Andy’s name was in the advertisements, it usually said “Andy Warhol Presents The Velvet Underground and Nico”, “Andy Warhol Presents Uptight”, “Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable”. So Andy’s name was very much in the forefront. And at that point Andy’s popularity in the press was much more high profile than it was three years earlier.

You know there was this period, it was back in the middle of the 60’s so it was ‘66 or ‘67 where all this stuff was going on, the art is going, the films were going, the Velvet’s were going, everything was going on, did you ever sense that it was getting out of control?

No, but actually when you look back at it, there’s a pattern. It’s like everyone is jumping ship, I mean Edie wasn’t there anymore, the Velvets weren’t there, I mean by spring of 67, the Velvets weren’t there anymore, you know. In September of ‘67 I went to Europe because I was invited to show one of my movies and I ended up by staying in Italy for 6 or 7 months. Then I came back and, you know, I didn’t have a job at that point and then Andy got shot.

What was the last film that Andy actually physically made?

The only movie that Andy really made after he got shot was “Blue Movie” with Viva and Louis Waldon. And there was a different feeling, because it was not really the Factory anymore, even though it was called The Union Square Factory, it was more of an office space, much more professional looking,

Who were some of the people that you brought into the Silver Factory?

I brought Paul Morrissey, Nico, Barbara Rubin, the VELVETS, Ronnie Tavel, and Mary Woronov, of course, she was a girlfriend of mine, and International Velvet, whose real name is Susan Bottomley, those are my two stars that I brought to the Factory. (laughs)

So you were like this guy…

It went something like that. I said, “Do you want to be in a movie?” (laughs) With Mary and Susan, I made movies of them, and then brought them to the Factory, so I could claim, saying,

“ I made the first movies of Mary and Susan!”.

Where were you when Andy got shot by Valerie Solanis?

That day I was on my way to the Factory to pick up a cheque because Andy was going to pay for the flyer for my first film retrospective at the Cinematheque. So I went to get Andy’s mother and brought her to the Hospital, and Andy was very grateful for that, and the following fall Andy called me back to work with him.

Art culture, American culture, and people behind that culture, let’s not say government, but let’s just say authorities on a responsible level, like government were looking at Warhol, and they were saying, OK to the Art, we love Andy’s Art, we love pop art, it’s a great expression of our culture, the movies, the movies are a bit kinky, the movies are a little bit weird but OK, that’s OK….

Well when you say they, who…?

I am talking about the government, the FBI…?

I don’t know if the government liked Andy’s art, they probably didn’t. They don’t understand Art. You know, Andy was not getting great press. Andy was getting a lot of negative press about his art as well as, I mean he probably was getting more interesting press on the movies even though it was probably not positive press. But the press coverage on the movies was more interesting than the art press cover. I mean I am telling you about the general press coverage.

I mean newspapers and magazines, maybe the art magazines gave Andy some respect but, certainly the Art world did, I mean the galleries whatever, I mean pop art was still very much, you know favored in a way. I mean it certainly eclipsed abstract expressionism. I mean the art world, the early art world was really in an uproar about pop art because it took the spot light off the art world that was generally concentrated on the abstract expressionism, and this all new art movement occurred and then all of a sudden things that we take for common can be art? That was very scandalous. Andy did something really interesting, also some of the other pop artists did the same thing to a certain, had similar ideas. And there was a convergence of those ideas, and that was because the media created that in a sense. In a sense the media created pop art, it became a mirror to the media, the story of pop art is really the story of the media looking at itself.

Back to this idea of the Silver Factory and all of these people who were there. There was this sort of collaboration. Andy had this ability to get people to do things, can you talk about that?

Yes I can to a certain extent. Andy whether out of calculation or sincerity behaved like a boy, Andy was always the boy, ok? He created a kind of aura around himself where, you know, people would just readily do anything for him. Andy was never a threatening person, he was always enthusiastic, he always made you feel like the centre of attention, he always made you feel important and therefore you would just want to do whatever. He said, “Lets do this, lets do that!”, and, we all, you know, got involved. So he had that kind of personality.

It wasn’t a manipulation at all?

Well it could be considered as a manipulation to a certain extent, but not out of a kind of maliciousness. No one said, “ Well how much is that?, what is the budget?, how much are you going to pay me?” That never happened, that never occurred.

And all the characters on this big joint film, all the characters on that film got along with each other?

Yes we all, pretty much got along with each other, we never really took ourselves seriously, which was a, it certainly was a, an attribute. And “Gee I am going to be in a movie!”, you know. Like whoever, I am busy doing my thing, whatever, writing poetry, you know, making movies, and I never thought, “Oh I am going to be in a movie!”, you have to think in terms of how the other people were thinking. Also at the same time about being in the movies, I am just using myself as an example, so it was a wonderful opportunity to, like an adventure, you know, like going on a journey, you know, you had, like that kind of adventurous feeling because it was.

It is a different kind of reality, you know. One never thinks, “Oh can I be in a movie.”, you know, so here it is, Andy Warhol giving people the opportunity, to basically be themselves!

It’s funny because what strikes me as being so interesting is that I believe that he really loved all the people that were in the Factory.

He loved what people were doing in front of the camera. Andy was always enthusiastic, and he was like, and Andy would just be, he would be, just a bunch of giggles, you know. He would just love it, you know, it was sort of like, I remember once when we were screening near to, the premier at the Bridge Cinema, which was on a street going along the Brooklyn Bridge. It was another one of Jonas Mekas’ touring cinema tanks, and we were previewing “Empire” for the first time. It was 8 hours long, no it actually was almost 12 hours long, and at some point people started throwing paper clips at the screen and, you know voicing their opinions out loud, and all kinds of weird shit was going on. And Andy turned to me in the back of the theatre and he goes, “Oh my God, do you think that they did not like the movie?”. And I was like, I didn’t know if Andy was putting me on or what; but it was a funny moment, you know, a candid moment.

What was the scene like at Max’s Kansas City?

Well, that was the real social watering hole, conveniently located abut a block away from the Union Square Factory. In those days it was the frontier. At night that neighborhood was dead, there was not a soul on the street. I go by there now at night it’s packed with people. It’s like New York City has a population explosion. But then, there were parts of Manhattan that were just quiet. That’s what made Max’s so great, when you entered the door of Max’s you went from this quiet neighborhood space outside into this party that was going on for the next five hours. Max’s would close at 4 in the morning, so it had a very self-contained party atmosphere.

Well, every night there seemed to be a party. Andy had a tab, so if we went there to eat it went on Andy’s tab, which he would then pay for at the end of the month. So we sort of cornered this area called the Round Table, which is basically the only round table in the back room, tables on the side or in the front part of the restaurant were booths, banquettes, so a lot of artists would go there. It was painters, writers, actresses, actors, it was just a very social atmosphere, it was incredible. I would go almost every night, always meeting new people, holding court, even when Andy was not there.

I think also that there was always something going on. You would shoot the film in the Silver Factory, you would run the film out, and you’d develop the film, you would get it back and screen it?

Right. Well we got screenings of the original footage, because it was reversal (stock). We would invite some friends, whoever was around. Andy would maybe call somebody, he would call Henry Geld…, and Henry would call somebody else. I would invite some poets over, whatever.

It was just a mix, mixture of, you know, people. Andy would always find people, you know, we would screen it, and then the next day go back with the film to the lab and get a print made.

Is there any particular screening that you can remember?

Oh, It was all blurred. I mean, we did so many screenings; it just, it became a such a routine you know, its all a blur. I mean it was just, was just, the new Andy Warhol film for that week. I mean we were making one movie a week here, you know, so it became, became routine but a, I can’t, I just can’t focus on any particular, I can’t remember.

Can you tell me about the screen tests, why did he do the screen tests?

We did the screen tests because, it started…I needed a publicity still, for my poetry-world adventures, and I thought, “What a nice idea to maybe do a publicity photo of me in some movie film, so I actually asked Andy to shoot a three minute (film roll) portrait of me, which became one of the subjects for the “Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys”, so basically that was all screen test stuff, the format. So Andy shot the film, we took it to the lab, I made a couple of stills, which I thought it came out very terrific, and then we just continued doing it.

Andy and I kept bringing people to the Factory. And I would shot some of them, Andy would shot some of them. There has been a bit of contention about that, as if it was a considered a true collaboration. In fact it was a book was published in ‘67 with his name and my name on it. But the film historian that has been conserving in catalogue and his footage still doesn’t consider it as a collaboration, so basically it was a white-wash., you know.

What in your opinion was the value of a screen test?

For me it was photo archiving; it was film archiving. Andy was doing a living portrait of somebody, a living record of that person, whoever that person was, whether they were invited to the Factory or they happened to come by. And we would say, “Let’s do your screen test.”.

The word “screen test” by the way was an attractive drawing card for saying, “Let’s do your film portrait.”. None of these screen tests really amounted to giving those people the opportunity to go on in the underground film world. It was kind of a parody on Hollywood. Hollywood would make a 30 second screen test, we would do a 3 minute screen test, you know what I mean, with a Bollex. Again it was the exaggeration, movie star, Hollywood star to superstar, it was an exaggeration.